Vanity Fair

July 1989

July 1989

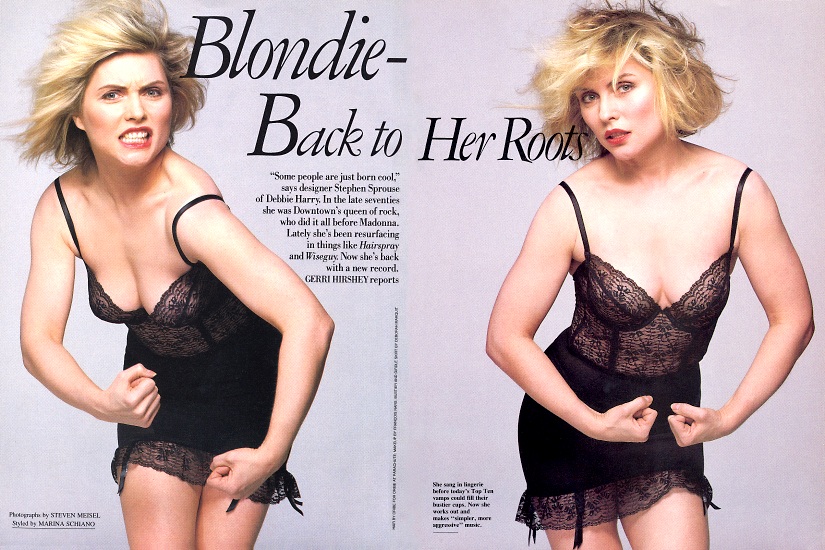

Blondie – Back to Her Roots

Written by: Gerri Hirshey

Photographs by: Steven Meisel

“Some people are just born cool,” says designer Stephen Sprouse of Debbie Harry. In the late seventies she was Downtown’s queen of rock, who did it all before Madonna. Lately she’s been resurfacing in things like Hairspray and Wiseguy. Now she’s back with a new record. GERRI HIRSHEY reports.

Someone is laughing in the Museum of Modern Art. Here on a dank spring afternoon, a real New York Story has slipped into the crowd for a sentimental journey through the Andy Warhol retrospective. Who is this, giggling in the temple?

She has strolled past the silkscreened Liz Taylors and Troy Donahues, on beyond Elvis. There she is, a peach in black leather, gazing at a pair of late-seventies spattered canvases labeled “oxidation paintings.” The sign says MIX MEDIUMS, but in fact they are the “piss paintings” according to someone who says he watched Factory denizens take aim and splatter. He says the paintings are so, well… authentic… that Andy was obliged to stack them away in a far corner, reeking of true eau de Downtown. Andy’s Cosmic Last Giggle.

Our laughing pop icon moves on, when suddenly she’s ID’d.

“Oooooh, such a FACE.”

A goony Manhattan fashion victim, trussed and buckled into pricey SoHo rags, has gone rigid as a bird dog, urging her companion to look, look, fergodsakes at that face.

“It’s Debbie Har-ry. Blondie.”

“No shit. Where’s SHE been for the last hundred years?”

Deborah Harry does a neat pivot and glides past them, double-sealed against such recognition, the signature  platinum hair tucked beneath a black jersey hood, over which she’s jammed a black leather cap. The body, small and slim again, is wrapped in a black leather coat over faded, too big jeans. Unobtrusive, down to the sensible tie shoes.

platinum hair tucked beneath a black jersey hood, over which she’s jammed a black leather cap. The body, small and slim again, is wrapped in a black leather coat over faded, too big jeans. Unobtrusive, down to the sensible tie shoes.

Nonetheless, people do stare at the face that became the flashy hood ornament for New Wave rock in the late seventies, the bottle blonde who stormed the stage at clubs like CBGB’s and tore off a tatty wedding dress to sing “Rip Her to Shreds” – nearly a decade before Madonna writhed through Venice like a video virgin in white. Harry was a Wrestlemaniac ere it was hip, a true Downtown demimondaine who shared her Bowery loft with feral cats and performed in a zebra-striped pillowcase her landlord plucked from the trash. She sang in lingerie before today’s Top Ten vamps could fill their bustier cups.

The Face is still quite beautiful, unretouched by lens filters or makeup. You could watch a movie across those cheekbones. They rise over wide, molded planes unmarked by four-plus decades, a fair amount of trouble, or what press agents call “character.”

“People seem to know me,” she says, “even when I’m not doing anything – like this last, um… low-profile bit. They know they know THAT FACE.” She laughs. “Whoever she is.”

Harry has turned a corner to find herself smack in front of “Marilyn Six-Pack.” Monroe in lavender. A mint Marilyn… lemon… one for all tastes. “Ah… Our Lady.”

As an adopted child in New Jersey, brunette Debbie Harry fantasized that her real mother was Marilyn Monroe. As a knowing adult on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, she mixed vintage sex-bomb peroxide with dark roots and New Wave wit and took it gold, then platinum on the record charts with her band Blondie.

I wanna be a platinum blonde, she sang at the outset, just like all the sexy stars | Marilyn and Jean, Jayne, Mae and Marlene | Yeah, they really had fun.

Yeah, yeah, and so did she, over 10 million records’ worth, with hit songs like “The Tide Is High,” “Rapture,” and “Heart of Glass.” Post-Monroe and pre-Madonna, she was a glam queen, Vogue pinup, punk poster girl. Few publications or college-dorm walls were immune to the lure of her look. She was Scavullo’d. Warhol’d. The Face was perfect Andy fodder, big, telegraphic, always camera-ready.

But now her friend Andy’s dead, nearly two years. The last Blondie tour was seven years ago, and then the band broke up. After her lover, Blondie guitarist Chris Stein, fell mysteriously ill in 1983 and she all but disappeared from the charts and the clubs, Harry became Manhattan’s most whispered-about rock M.I.A. since John Lennon dropped out to bake wheat bread.

“Where have I been?” Harry laughs, a deep, subdiaphragm huh-huhhhhhh. She is standing by a wall of plump shellacked Marilyn mouths, this woman Newsweek once called a “klutzy guttersnipe Garbo.”

“Just write, ‘She’s living alone. Somewhere below Forty-second Street.'”

The FACE that was 1980 has been flickering almost subliminally throughout this decade. In ads for Hush Puppies, Sara Lee, and Revlon. In supporting movie roles – married to Sonny Bono in John Waters’s film Hairspray, as a housewife in Union City. She got her best notices for her performance in David Cronenberg’s cult  shocker Videodrome. Harry popped up two years ago with an album, Rockbird, and a cotton-candy single “French Kissin’ in the USA.” That was her, singing a lambent remake of “Liar, Liar” on the sound track of Jonathan Demme’s Married to the Mob, with an accompanying gangster video for MTV. And just this spring she joined fellow rockers Mick Fleetwood and Glenn Frey for a run of episodes on Wiseguy, CBS’s hit Mob-u-drama. She played a has-been rock star making a comeback. Harry was charming – and convincing – as Diana, a pop siren becalmed in a Jersey Meadowlands saloon, singing standards for a bar glass full of change.

shocker Videodrome. Harry popped up two years ago with an album, Rockbird, and a cotton-candy single “French Kissin’ in the USA.” That was her, singing a lambent remake of “Liar, Liar” on the sound track of Jonathan Demme’s Married to the Mob, with an accompanying gangster video for MTV. And just this spring she joined fellow rockers Mick Fleetwood and Glenn Frey for a run of episodes on Wiseguy, CBS’s hit Mob-u-drama. She played a has-been rock star making a comeback. Harry was charming – and convincing – as Diana, a pop siren becalmed in a Jersey Meadowlands saloon, singing standards for a bar glass full of change.

“It’s fiction,” she says of the TV role. “Good fiction.”

In the fiction, Diana/Debbie resurfaces with a hot new single. The song, “Looking in the Bright Side,” is Harry’s, and it just may be on her new solo album, due in the stores any day. It just may be the single. She recorded the album in California and London, with some new friends, like the Thompson Twins, and some old stalwarts, like Chris Stein and former Blondie producer Mike Chapman. She says she’s tried to make it a bit more salable for today’s corporate playlists.

“Simpler,” she suggests. “More aggressive.”

This from a woman whose first solo album, Koo Koo, pictured huge acupuncture needles skewering her lovely head. She acknowledges that her career has always been more instinctive than calculated: “I’m not very smart, businesswise. I can really lapse OUT THERE and get totally… God knows what.”

Harry and Stein started writing songs for the album nearly three years ago, and began recording in fall ’87. “All that stuff is over a year old now, which is sort of depressing,” she says. The holdup? They had to switch record labels. And management. Again.

“You know this business,” she says.

You have to keep a sense of humor, no matter what. Which is why she’s thought up this title for the new record.

“I want to call it ‘Deaf, Dumb, and Blonde.'”

“Oh my God, oh, c’mere!”

Harry has a coat sleeve, tugging me toward a huge Warhol silkscreen of S&H Green Stamps. They’re trading stamps, the great sixties come-on that had millions of sticky-fingered suburban moms dreaming of four-speed blenders and cute chip ‘n’ dip bowls.

“I don’t believe this. I used to work in one of those places. At an S&H redemption center near Paramus.”

It was on New Jersey’s Route 4. She presided over happy, if messy, consumer redemptions. “I wore little rubber things on my thumbs to separate the pages. I handed out toasters. Lawn chairs. Cookie jars. TV trays for your frozen dinners…”

She is ticking off other jobs she has held. Waitress. Playboy Bunny. Shampoo girl. For the briefest stint, she barked Jersey housewives through aerobic drills at a European Health Spa.

She stops and takes another look at the canvas.

“Every performer kind of slides along in other jobs to get by until it happens. And so I got to be a rock singer. But, whoooeee, first I was, um… AN AMERICAN GIRL!”

Such a beautiful baby. Folks told Catherine and Richard Harry they should send snapshots of her to the Gerber baby-food people. A puss like that could sell a lot of strained peas.

They declined, happy just to have the Miami-born infant they got at three months old, when her natural mother gave her up. They raised her Episcopalian in Hawthorne, New Jersey. She was a sweet, tractable child who sang in the church choir and turned mulish only when it was time to buy school clothes. Even in grammar school, she saw visions they didn’t sell in chain stores.

“I was never really satisfied with how I was supposed to look,” she says. “My mother and I had huge battles. When we used to go shopping it was hell. She’d want me to wear little blouses with round collars and sweaters and I’d be looking at black turtlenecks. At that age – eight or nine – you can’t be doing that. It was not the look in those days to be so, um, severe.”

What made her so visually precocious?

“It was just something that was in my head or eye. Something that was… severe.”

It got worse in high school.

“I had a hairy vest before Sonny and Cher, I swear to God. I made this hairy thing and my girlfriend said, ‘You can’t wear that, it looks like a dead DAWG.'”

She says she styled it, cut deep armholes and a V neck into a matted piece of acrylic fake fur.

“It was really disgusting. And I loved it.”

Fuzzy and defiant, she strode the halls of Hawthorne High. Happily, the classy Face and a fling at baton twirling redeemed any teen fashion crimes. Her classmates voted her Best-Looking Senior, Class of ’63.

In 1987, Harry would show up with her prom pictures when John Waters cast her in the role of the sixties hausfrau/bigot in Hairspray. As the odious Baltimorean Velma Von Tussle – “Miss Soft Crab of 1945” – she gamely submitted to teasing, lacquer, even bleached her famous roots, trading comb-out laments with her co-star the late, great Divine. Waters says that despite “hairdo injuries” on the set, Harry was a swell sport who understood the loopy Zeitgeist of the Mashed-Potato Years in East Baltimore.

“She got it,” he says. “Debbie’s no snob. She’s beautiful and talented and glamorous, but she’s lived in the real world. I mean, she wasn’t a stranger to the bouffant.”

Across from the Green Stamps, Harry is having another small Andy epiphany, in front of a painting done to look like an unfinished paint-by-numbers still life. It’s titled Do It Yourself.

“I just wrote a song by that title.”

She laughs. Again.

“I hope you’re going to make this funny,” she says. “‘Cause it is. Andy. Jeez. Sometimes I think I’m just a child of his imagination.”

She really misses Andy and his determined celeb choreography. But when she first encountered the Warhol mob, it was a boho nightmare. This was in the mid-sixties, when, after a two-year stint at junior college, she left her teasing comb in Hawthorne and crossed the Hudson to lower Manhattan.

“It was the beginning of the hippie invasion,” she says. She was living in an Italian/Ukrainian neighborhood on St. Marks Place, singing with a folkie group called Wind in The Willows, and paying the rent by picking up sticky change at that scene-maker’s boite, Max’s Kansas City. Nightly, gaggles of Warholites like Nico, Ultra Violet, and the protean Velvet Undergrounders flung themselves into the scarred black booths and made her cry into cocktail napkins.

“I was just a hysterical waitress,” she says. “I was so timid in those days. They were all so wild, they’d come in wrecked out of their brains, wanting a zillion things. I was extremely shy, and I was dealing with a lot of things I had to conquer within myself.”

One of those things was a brief heroin addiction – supported in part by that stint as a Playboy Bunny. She kicked at an artists’ colony near Woodstock, returned to Manhattan, and became obsessed with joining a girl group called Pure Garbage. They let her when they reinvented themselves as a trio called the Stilettoes. She says she walked back into Max’s with a bolder step, “serious makeup,” and outfits they’d never dare sell at Victoria’s Secret. They sang original songs like “Dracula, What Did You Do to My Mother?”

And the timorous ex-baton twirler?

“I guess I left her in the parking lot. Somewhere around Paramus.”

We are looking at car wrecks. Decapitations. Suicides. Electric chairs. Warhol’s disaster series, silkscreened off grisly news photos.

“Eeeeesh.”

Harry makes a face, then punches me in the arm.

“I just remembered something weird.”

It’s about the downside of Downtown in the early seventies, on an airless summer night when she left friends at a bar and tottered up Houston Street on nosebleed platform shoes.

“It was real hot. And I think I’d done something dumb like eat a Quaalude. This guy pulls up in a Volkswagen Beetle, cute guy. He says, ‘You need a ride?’ Like a jerk I get in. And it’s really hot. I realize he’s got all the windows rolled up. And you know what?”

She thwacks her forehead.

“There were no window or door handles on the passenger side! Ugh, what a moment. Somehow, God knows how, I wriggled my hand out the three inches my window was open and grabbed the door handle on the outside. He saw me and swung the car – violently – drove up over that median thing on Houston. The door swung open, THANK GOD…”

The scenario end with Harry spraddled in the middle of Houston Street, platform shoes dangling clunkily over the curb.

“Flat on my ass.”

In hindsight, she’s glad she didn’t end the night in an N.Y.P.D. body bag.

“Hey,” she says, “Ted Bundy drove a Volkswagen, didn’t he? You think it was Ted Bundy?”

Shortly after this episode, a Lancelot would ride into her life, a boy to be Blondie with. They met in 1973, when she was performing with the Stilettoes, vamping on a sawed-off pool table that served as the stage in a West Side burger bar. Chris Stein remembers that she had short brown hair and a touch of glitter. She says he stared, and she noticed. He was something.

“Um, Chris,” she says. “He was a guy who used to wear these snakeskin pants really tight and patched. With embroidered crushed-velvet tops open low. With tons of necklaces and his hair was very long and he wore eye makeup – black – like Alice Cooper.”

Later, she’d sing it: When I met you in the restaurant | You could tell I was no debutante.

He was a sometime band roadie from Brooklyn. A brainy guy with a sense of history and an irresistible restlessness. They formed and re-formed bands, dogged the Downtown clubs. It was love on the Bowery: bed at dawn, breakfast at dusk, dinners with headbangers, artists, punkettes. They survived poverty. Bad management. Band wars. Success.

“Really,” she says, “let’s not talk about this part too much.”

Harry has stopped in front of Warhol’s tabloid-newspaper series, where a professorial-looking couple stands reading Daily News headlines aloud.

EDDIE FISHER BREAKS DOWN

In Hospital; Liz in Rome

“Eeeeesh,” she says again.

A few years ago, Deborah Harry lived some tabloid times, like the ones depicted here in Warhol’s shrieking-headline canvases.

They began in 1983 when Chris Stein fell dangerously, almost fatally, ill with pemphigus, a rare genetic disease. He’d needed oxygen tanks on the last Blondie tour, and he got worse. And worse. Their 110-m.p.h. life hit a nasty wall of lab tests and baffled specialists. It was beginning to read like a rock ‘n’ roll Love Story.

When the illness struck hard, Harry never left the island of Manhattan while she tended Stein, three months in the hospital, three years at home. She slept on a cot in his hospital room, ducking paparazzi who still managed to snap her scuttling through back doorways, looking haggard, and uncharacteristically zaftig. The famous do was covered with a babushka.

New York tabloids ran the photos, and made her into a New Wave Garbo. Rumors burbled in the rock world: Debbie’s dying. Chris is dying… Music editors sent reporters out for the big destructo feature that never materialized. It was, after all, a very old story: after eleven years together, she had simply stood by her man.

“Period,” she says. “No big deal. No martyr stuff.”

Apart from the real terrors of Stein’s illness, she says, the downtime was in many ways restorative. “Everything had been so intense. Just thinking about it I’m getting dizzy. There was no escape, no respite. What really brought me down to earth was Chris being sick. When that happened, I just said I don’t have time for this bullshit. And I just washed it out of my character.”

It would be nice to say they lived happily ever after, but once Stein’s recovery was ensured, the couple split up, nearly two years ago. Harry moved out of their West Side penthouse, the one with the zebra-patterned kitchen floor and the swell terrace above Fashion Avenue.

“So, yeah, I’m a single girl. Again.”

As she walks along, Harry has been absently shifting the burdens she declined to check in the museum coatroom: an armload of stuffed manila envelopes from her manager’s office, and a boxed appliance that still has bits of giftwrap clinging to it. It’s a present from her father, a small coffee-maker designed for the single life. The label reads: “One Cup at a Time.”

“No drama, no dirges, please,” says Chris Stein, who has been well enough to prowl the clubs and play guitar for over a year now – something he and Harry still do together. He hopes they’ll tour behind her album, says they really enjoyed the show they did last year with a band they called Tiger Bomb. Recently they teamed up with their old pal Joey Ramone at the Ritz.

“It was a Friday the Thirteenth Inquisition Party,” says Stein. “They beheaded Nixon onstage. And [heavy-metaler] Lemmy from Motorhead was the Grand Inquisitor and he sat on a throne. I always enjoy those little things…”

He and Harry still indulge in their fifteen-year obsession with pro wrestling as well. Wrestlers often hung out backstage at their shows, “young gigantic things,” Harry remembers, “with rock ‘n’ roll hair.” They’ve maintained their wrestling friendships, and sometimes they take their friend punk poetess Lydia Lunch along to see Macho Man and Rowdy Roddy Piper two-step at Madison Square Garden. Not too long ago, the mighty Queen Kong saw them sitting ringside and came down to pummel Stein’s head – bimbamboom – between her titanic bazooms.

Behind the laughs and the cartoony nights out, there have been tough times. Living apart and working together can be a strain, but neither of them wants to yak about details. As they’ve written in a called “The End of the Run,” Once that tape starts playing, | It’s too hard to make it rewind.

They say the song is not so much about their love affair as about life on the pop charts – though the two were inseparable for them. Both of them agree the lyrics have to do with the seductions and treacheries of Style.

“Whatever scene people are involved in, it was always better six months ago,” says Stein. “People are always saying, Aw, but now it’s really fucked up. Everybody’s longing for some forgotten situation which was glorious just by the fact that it’s a fallen into memory.”

Lava lamps. Beige lipstick. Da doo ron ron.

“I’m not into nostalgia,” says the former Girl of the Minute.

Nobody has ever had to tell Deborah Harry what to wear, and it is there, in the ineluctable minuet of rock and style, that the Green Stamp redeemer proved she was something special, something unusual. An American Girl who could pull her Self together.

It should be noted that Harry, always ahead of the curve, made her mark before the great boutiquing of Self that has marked the MTV years – a merchandising millennium in which department-store chains have cashed in with Madonna-wannabee shops and a wacky retail homage to Cyndi Lauper. It’s couch-potato shopping, since buyers and stylists do the prospecting. But when Debbie did Downtown, it was strictly hands-on.

She talks easily and enthusiastically about visual style, understands its seductions. She is hip to the lasting social value of being laughed at on the street: “Styles change and somebody has to do it. I had a sense that the way things melt down, aspects of fashion that were spectacular or crazy or bohemian to the freak nature would wash down and become salable, that everyone would want it.”

When she started wearing platform shoes in the seventies, even Puerto Rican hookers on the corner of Fourteenth Street howled. Hey, chica, nice SHOES.

“Within a year,” she says, “everybody who had hooted in laughter was wearing HUGE ones.”

Often, she found her treasures thrift-shopping with that groundbreaking male glitter group the New York Dolls. It could be hazardous, she says, because those covetous big galoots would tear a chenille bed jacket right out of your hands.

“David Johansen had a great eye for cute tops.”

She was with the Stilettoes then, and the look was half glitter, half lingerie, mix ‘n’ match. More than once, she dressed out of Dumpsters, plucking fabric remnants from the bins outside Lower East Side sweatshops. For Harry, style has always been a function of current economics and her whim of the moment. “I’ve just always had this problem with timing.” Being “severe” didn’t play well in suburban Jersey in the early sixties. But, as it happened, Severity redeemed the silly seventies. Those leisure-suited days sorely needed our style heroes, who rode in clothed in safety-pin chain mail of Anti-style. Suddenly, Harry’s schizy retro-couture made her a leading-edge style moll with a look so cool, so desperately desired, that she transformed the fash-addict audience at L.A.’s Whisky a Go Go instantly – like some punk Tinker Bell – circa ’77.

“Everybody was there in bell-bottom pants,” she remembers. “And we did a couple of shows. Then the girls were there in tight pants and minis. They had SCOURED the secondhand stores. It was bing, bang, BOOM, shooooooom.” Harry lunges, imitating the greedy grab of Melrose Avenue thrift-shoppers, plucking chicken slacks off a rack.

“It was funny. It was cute. It was really overnight.”

As she’s written in a song for her new album: A torn T-shirt made it all dangerous again.

Punk and New Wave challenged the polyester hegemony of disco wallpaper and M.O.R. easy listening. Chris Stein explains: “The whole New Wave thing we came out of, CBGB’s and stuff, it was sort of a backlash against all these faceless bands, Chicago, the Allmans. Everybody sort of invented this personality cult. The Ramones, Television, all these groups showed up with a lot of personality.”

And torn T-shirts and geeky narrow-lapel suits. Says Harry, “The only way to make everybody [in the band] look good and cool was to go to secondhand stores and get really tight things, little suits with the narrow lapels, small-collared suits which nobody was wearing. I was dressing like a boy, cross-dressing.”

Other art-school types like Talking Heads and Patti Smith sported inch-wide ties and tiny tab collars as antidotes to the pointy Saturday Night Fever nightmares – those huge, double-stitched numbers that flapped like plastic gas-station pennants halfway down the chest.

Blondie’s metaphors were as mixed as its wardrobe. Lyrics were patched from literature and soap ads, for songs like “Kung Fu Girls” and “The Attack of the Giant Ants.” Surf music, girl-group la-la, punk guitar slashes, and jungle drums. Rap and reggae. They had great fun, and left the semiotic analysis to fusty rock critics.

“We never gave it too much thought,” says Harry.

“We never did any sort of deliberate thing,” says Stein. “Just certain style elements that we thought worked.”

“Some people like Debbie are just born cool, I guess.”

This from designer Stephen Sprouse, who added his Downtown professionalism to Harry’s Blondie look – in a very ad hoc way. Theirs is still the greatest of friendships, forged of mutual kindness and genetic cool. They were neighbors in the mid-seventies, sharing the kitchen and bath between their Bowery lofts. This was the Lower East Side before you could buy pink peppercorns on Avenue A, when loft ads read “toilet-fixture fee” instead of “marble Jacuzzi.”

“I met her in the kitchen,” Sprouse says. “Somewhere near the toaster oven.” He was painting, designing, a rock ‘n’ roll former art student who had worked with Halston and his Uptown ladies. He says he first saw Harry performing at CBGB’s, singing “Heat Wave” in a way that made Linda Ronstadt sound like a pruney temperance leader on her hit version. But they got to be friends because of the cats.

“There were backyards that made a courtyard, and all these alley cats were interbreeding,” says Harry. “Hundreds and hundreds. I don’t know if they ate rats or whatever, but they were tough, all scarred, one eye hanging out. One ear. We’d see these raging battles.”

Somehow, during the winter, one of them got trapped between the floor of Sprouse’s place and the ceiling of the loft below.

“I’d still be sleeping and I’d look up and there would be Debbie, feeding the cat.”

She pitched Tender Vittles into a hole beneath the floorboards near Sprouse’s ear. He thought it was touching – and practical.

“She didn’t want him to die. And rot there.”

Along with Chris Stein, they got to fooling around – with hair, makeup, junk clothes.

“Steve had some stuff because he had worked for Halston and he knew all these models and elegant women,” says Harry. “He’d been dressing them, and he had a few pieces left over from that. He liked the idea that we dressed sixties, which was basically out of necessity.”

Later, Sprouse would become a darling of the fashion press for his neat, eighties distillations of sixties style elements. Mick Jagger would ring him in a panic a few nights before Live Aid for a yellow jacket modeled on the old Stones getups.

“Steve had that clear perspective,” says Harry of those early years, “and it all came together.”

One memorable improvisation: a minidress whipped up as the band was about to leave for a British tour. “I got this thin, bodysuit-type thing,” Sprouse remembers. “I turned it upside down and cut out the crotch and made it into this one-shoulder dress.”

Harry hung razor blades from the hem, and rock ‘n’ roll badges. It became a poster shot, a punk book jacket, a tightly wrapped silhouette that echoed through the Alaia eighties.

By the time Blondie had three albums out, there was more money, and Sprouse was able to use the big silkscreens he made from video static and test patterns, transfer them to good fabrics, and wrap his famous friend in them – then charge the record company. During her quiet years, he gave her many pieces from his short-lived ready-to-wear collections – the Keith Haring graffiti’d Bible-page prints, the Day-Glo jackets. Following the collapse of his second ready-to-wear line and shop, his friend Debbie Harry has been supportive, gracing his gallery show (silk-screens of Iggy Pop on the cross), and just hanging out like old times. Sprouse says he is working on a book about the last ten years of rock and style, and of course she’ll have to be a part of it. Along with Andy Warhol, Debbie Harry, he figures, is the best curator/mannequin of his fashion work.

“Andy – or someone from the Factory – has the first two years of the stuff,” he says. “And Debbie has the rest.”

“Here’s the thing,” Harry is saying. “Some people are just better at selling.”

You can be light-years ahead of the curve, but some folks are born salesmen, and others just get these weird ideas.

“You know, I never put it together until just now. Not only my father but his father was in sales.”

Her grandfather sold shoes; her father worked in the garment center. Her father used to talk about his work a lot. When he showed up in Seventh Avenue showrooms, he never sold hard. “He was very casual about it,” Harry says. “He always said that if people want something they’re going to buy it.” In hindsight, she’s often said she’s glad she never had to come up with a hard-sell look. “I mean, if I had to start today, I don’t know what I’d do when someone told me I had to have an image.”

She says she’d still like to fool around, “take those terrible Arnel suits, those floral shirts with long pointy collars… drag all that shit out, but do it nicely.”

She’s still got her platform shoes – they’re coming back in a very demure way in Paris. Says Harry, “Nothing’s new before it’s old, real old.”

And therefore new again. Ask her for an overall impression of the workings of rock style and she doesn’t stop to cogitate.

“IT’S COMPOSTED!” she hollers, then laughs.

Things reconfigure and bubble back to the surface.

“COMPOST!”

On our way out of the Warhol retrospective, we pass a huge multiple silkscreen of Leanardo’s Mona Lisa. Harry jerks a thumb at it.

“Now, that’s the real Madonna.”

Out on the street, Harry is headed home. Downtown. There she is, arm up in the rush-hour traffic on Sixth Avenue, ahead of the curve and out on a limb. Calling to mind a new lyric that had blared out of the demo tape in her manager’s office a few hours earlier: Here comes the twenty-first century. | It’s gonna be much better for a girl like me.