THE INDEPENDENT

TUESDAY REVIEW

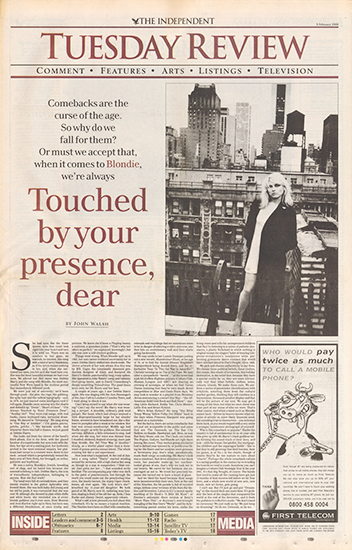

Comebacks are the curse of the age. So why do we fall for them? Or must we accept that, when it comes to Blondie, we’re always Touched by your presence, dear

BY JOHN WALSH

She had eyes like the Snow Queen, eyes that could look right into your heart and turn it to solid ice. There was no comfort in her gaze, no warmth, no interest. She sang with a kind of nervy blankness, as if the lyrics meant nothing to her, and, when she narrowed her eyes, you felt as if she must hate you. She was the most beautiful woman we had ever seen. We adored her. Her name was Debbie Harry, and she sang with Blondie, the most successful New Wave band in the restless period that immediately followed punk.

We were just out of university; we’d been through punk – the pins, the rage, the gobbing, the spiky hair and the radical typography – and, in 1978, we just wanted some intelligent rock’n’roll again. Blondie came sassing into the charts and dished it up: “Denis”, “Heart of Glass”, “(I’m Always Touched by Your) Presence Dear”, “Sunday Girl”. They were real songs, with real hooks, classy keyboard runs, torrential drumming. We danced to “Dreaming”. We sang along to “One Way or Another” (“I’m gonna getcha, getcha, getcha…”) like karaoke nerds. And whenever there was half a chance, we just gazed at Debbie Harry.

She looks out from the sleeve of the band’s third album, Eat to the Beat, with the glazed hauteur of a supermodel, her eyes toxic with disdain, her lips set in a soaring pout, her eyebrows arched in the most minimal enquiry, her platinum hair swept in a couture wave down to her neck – around which is proprietorially twined the hairy arm of Chris Stein, her Svengali, co-writer, guitarist and boyfriend.

He was a sultry, Brooklyn-Jewish, brooding sort of chap, and we hated him because she seemed to belong to him. Debbie Harry, the icon of transatlantic independence, belonging to anyone. How did that work?

The band were full of contradictions, and they mostly resided in the gutter Aphrodite who fronted them. She was both baby-doll young and too old for punk; it was rumoured that she was over 30, although she dressed in plain white shifts and white boots; she reminded you of every blonde goddess you’d ever seen, from Monroe and Jean Harlow right up to Nico, but hers was a different blondeness, at once trashy and pristine. We knew she’d been a Playboy bunny, a waitress, a quondam junkie (“That’s why her skin’s so perfect,” we explained, knowingly), but she was now a self-created goddess.

The band were full of contradictions, and they mostly resided in the gutter Aphrodite who fronted them. She was both baby-doll young and too old for punk; it was rumoured that she was over 30, although she dressed in plain white shifts and white boots; she reminded you of every blonde goddess you’d ever seen, from Monroe and Jean Harlow right up to Nico, but hers was a different blondeness, at once trashy and pristine. We knew she’d been a Playboy bunny, a waitress, a quondam junkie (“That’s why her skin’s so perfect,” we explained, knowingly), but she was now a self-created goddess.

Things went wrong. When Blondie split up in 1982, her solo career wobbled uncertainly for 10 years. Debbie Harry shifted into shock mode. The sleeve artwork of her solo album Koo Koo was by HR Giger, the intestinally obsessed production designer of Alien, and featured Ms Harry’s cheeks punctured by long, rusty spikes. She appeared in John Waters’ camp and rubbishy Hairspray movie, and in David Cronenberg’s deeply unsettling Videodrome. The good times were over, for Ms Harry and her fans.

A couple of years ago, I saw Debbie Harry again. She was singing with the Jazz Passengers at the Jazz Café in London’s Camden Town, and I went along to check it out.

Can I bring myself to say what she was wearing? Can I say the word? Ms Harry was wearing a jumper. A sensible, ordinary, pink wool jumper. Her head, which had always seemed a little disproportionately large for her slender frame, seemed to have broadened out, like a Hallowe’en pumpkin after a week in the window. Her hair was mousy-nondescript. Middle age had finally caught up with the goddess. She seemed nervous, diffident, a little reluctant to sing. And when she did sing, her voice was thinner than I recalled, etiolated, drained of energy, more pale than blonde. She did “One Way or Another” slowly, as a wistful plaint rather than a statement of gonna-getcha sexual intent. The whole evening felt like a sad experiment.

Now look what’s happened. At the end of January, a song called “Maria” started winding around the airwaves, with a high chorus line sung as though by a nun in suspenders (“Mah-ree-ah/ Just gotta see her…”) that sounded eerily familiar. The accompanying pop video was dark to the point of pointlessness, but through the murk you could make out the penetrating blue eyes, the trashy barnet, the sharp Tiger cheek-bones, all over again. “My God, who’s she?” breathed my 11-year-old daughter. We both gazed at Ms Harry, now 53, radiating sexy hauteur, singing in front of the old line-up, Stein, Clem Burke and Jimmy Destri, apparently reborn.

What’s odd is how pleased you feel about this comeback. It’s by no means a typical reaction. The Nineties have been so filled with comebacks, retreads and recyclings that we sometimes seem to be in danger of entering a retro-universe, one that hits an evolutionary wall and then starts going backwards.

We may smile to see Lonnie Donegan putting out a new record, Muleskinner Blues, at the age of 70, or to find the Sixties crooner Englebert Humperdinck being dusted down, and the rebarbative Tony “Is This the Way to Amarillo?” Christie turning up on Top of the Pops. We may utter a sympathetic “Awww…” at the news that a job lot of effete Eighties poseurs (Culture Club, Human League and ABC) are sharing an evening of nostalgia, or when we find Duran Duran insisting that they’re very much direct competition to Blur and Oasis these days. We may look in wonder at a playbill from Wembley Arena announcing a concert this May – “the All-American Solid Gold Rock and Roll show” – starring Little Richard, Bobby Vee, Chris Montez, Little Eva and Brian Hyland.

Who’s Brian Hyland? He sang “Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini” back in the days when Princess Margaret was going around on a motorbike.

But the fact is, there are some comebacks that are just not acceptable to the public and some that are. The Osmonds, no. The Bay City Rollers, no thanks. Hawkwind, nah. Bros, no way. The Pogues, God yes. Any Blondie are right there among the yeses. They were a group you never had to defend your interest in, or justify your liking for. Ms Harry and her acolytes were geniuses at throwaway pop; that’s what, paradoxically, made their songs so enduring. Ms Harry’s look was a construct, that drew attention to her black roots, her pancake make-up, her machine-tooled gleam of sex; that’s why we took her to our hearts. We cared for her because she encouraged us not to. We loved her precisely because she turned out to have a heart of glass.

And we liked the band because their songs were incontrovertibly their own. Now, at the end of the Nineties, the hit parade is full of recycled songs, listless cover versions of hits from the Sixties and Seventies. Listen to 911’s recent spotty warbling of Dr Hook’s “A little Bit More”, or Emmie’s antiseptic disco version of Roxy’s “More Than This”, or Boyzone’s overwrought mangling of the Bee Gee’s “Words”, and the forty-something parent smites his brow, stalks the living-room and tells his unimpressed children that they’re listening to a series of pathetic simulacra, a plastic Echoland in which nothing is original except the singers’ habit of wearing telephone-receptionist’s headpieces while performing gymnastic dance routines that would have seemed dated to Pan’s People, circa 1968.

We pick and choose authenticity in our lives. We choose these political beliefs, these clothes, this music, this shade of terracotta, this holiday destination, in the belief that, because they have a special reality for us, they are more intrinsically real than other beliefs, clothes, notes, colours, islands. We make them ours. We perform a series of passionate identifications with artefacts, selecting them from the cultural market garden, thinking they will combine in a harmonious, thousand-petalled display and that will be the picture of our soul. We may get it wrong all the time, but what we once chose was once part of our sense of who we were. That’s what counts. And when a band such as Blondie comes back – driven by heaven knows what impulse of artistic or, more likely, financial need, but sounding true to themselves – you welcome them back, as you would regard with a wry smile a younger, handsomer photograph of yourself.

Why is this comeback so popular? Maybe the country is full of sentimental 35-to-45-year-olds who grew up with Ms Harry’s trash-goddess vocals forming the sound-track of their lives, and now – with the house, the garden, the mortgage, the children and the asparagus kettle – like to feel they’re still grooving; that their heroine, their ice queen, is at No 1 in the charts, though of course they’re far too mature to care about “charts”. Perhaps the whole comeback culture is a saying-goodbye to the century by re-treading the boards we trod in youth. Somehow, you can’t imagine a Culture Club Nostalgia Tour in the year 2001. It’s that Big Nought, of course. The bands that used to make all the running have got just 10 months of final encores left before we hit Year Zero, and a whole new world of new acts, new music, new art forms, gets going.

I can’t say. But I’ll just go and put “Dreaming” on the record deck one more time. It’s probably the best of the singles that conquered the world at the end of the Seventies, and it finds the goddess in reflective mode: “We don’t stand on ceremony/ We just walk on by/ We just keep on dreaming”. So do we, Deborah, so do we.