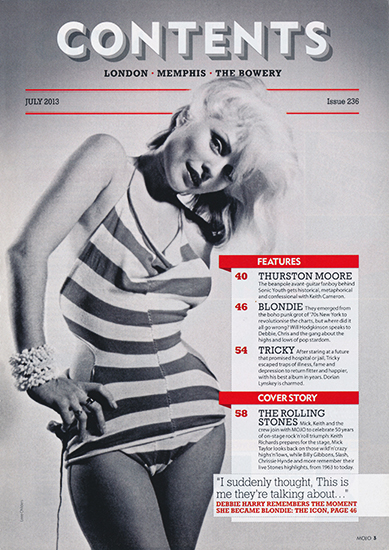

Page 3 – CONTENTS – photo by Leee Childers

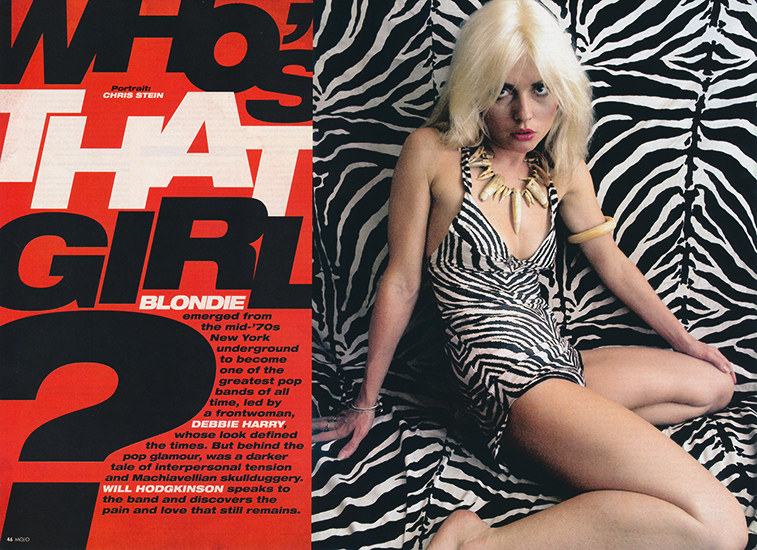

WHO’S THAT GIRL?

Portrait: Chris Stein

BLONDIE emerged from the mid-’70s New York underground to become one of the greatest pop bands of all time, led by a frontwoman, DEBBIE HARRY, whose look defined the times. But behind the pop glamour, was a darker tale of interpersonal tension and Machiavellian skullduggery. WILL HODGKINSON speaks to the band and discovers the pain and love that still remains.

THE GRAMERCY PARK Hotel, New York, spring 2013: Debbie Harry and Chris Stein take in the changes to a place they called home for the second half of 1977. Artworks by Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat line the walls of the terrace bar, where smart, fashionable waitresses glide about and attend the needs of stylishly moneyed guests with an impeccable Manhattanite professionalism.

THE GRAMERCY PARK Hotel, New York, spring 2013: Debbie Harry and Chris Stein take in the changes to a place they called home for the second half of 1977. Artworks by Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat line the walls of the terrace bar, where smart, fashionable waitresses glide about and attend the needs of stylishly moneyed guests with an impeccable Manhattanite professionalism.

“We lived here for a while, it was such a dump,” says Debbie Harry, staring bleakly at a Warhol screen print of the basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. “We were here for a few months after our apartment on the Bowery burned down. You went past the lobby, all the way to a tiny elevator at the back of the building, which led to grimy rooms with kitchenettes. That’s where we were.”

“That was back when people were too scared to come to New York,” adds Chris Stein in his ungentrified Brooklyn drawl. “Everyone thought they were going to get their throats cut and their wallets stolen. Now all that has changed.”

“True,” says Harry, before adding with the faintest of smiles, “although Chris and I are still sharpening our knives.”

A ONE-TIME BOHEMIAN STRONG HOLD THAT has survived and scrubbed up against the odds, the Gramercy is a suitable place to meet Blondie. This is the band that emerged from the New York underground scene of the mid-’70s to become arguably the coolest pop act of all time, with a roster of irresistible songs and a front woman as sexy as she was – to use a word that still mystifies her – iconic. Behind the pop glamour, however, lies another story, a lesser-told tale of interpersonal tension, Machiavellian skullduggery and disastrous financial mismanagement. It’s also one of romance, excitement and ultimately a strange sort of contentment, with former lovers Harry and Stein at the heart of it all. And it began with a love affair with a city they both still call home.

“I started coming into the city in my very early teens and it was quite an adventure,” says Harry, the adopted daughter of gift shop owners in Hawthorne, New Jersey. “I don’t think my parents ever knew. I would tell them I was going shopping, get a dollar bus ticket from Port Authority, and head down to the West Village. I wanted to hang out in all those cafes and clubs and I was very interested in poets like William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. It was another world from my high school, which was filled with greasers, tough guys. I wanted to be a beatnik.”

While Harry was on her clandestine investigations into New York’s subterranean underbelly, Chris Stein, son of Jewish hard-left intellectuals, was being inducted into the world of hip at a young age. “You know how kids these days are disdainful of Justin Bieber? Pop songs like The Locomotion had a visceral impact on me as a kid but I knew they were uncool, so I was happy to discover Bob Dylan and the whole West Village folk scene. I’d go down there and Richie Havens would be hanging out on the street corner. Then, when I was 15, I was with a friend in Washington Square and we spotted Keith Richards getting into a cab. After that, I was in bands.”

Stein briefly played guitar in short-lived garage band The Morticians, which later became the baroque pop quartet The Left Banke, but his big moment came when he and some friends from Brooklyn opened up for The Velvet Underground at the Gymnasium in 1967. “That was the high point of my youth,” he says. “There were maybe 30 people there.”

Harry, raising an eyebrow, adds, “He’s been trying to live up to it ever since.”

Before Blondie, Debbie Harry had been a singer in whimsical folk rock band The Wind In The Willows, a secretary, a waitress at Warhol hangout Max’s Kansas City, a Playboy bunny, and one third of camp, theatrical girl group called The Stilettos. It was at The Stilettos’ first gig in October 1973, at a small bar on 24th Street called the Bobern Tavern that Stein met Harry.

Before Blondie, Debbie Harry had been a singer in whimsical folk rock band The Wind In The Willows, a secretary, a waitress at Warhol hangout Max’s Kansas City, a Playboy bunny, and one third of camp, theatrical girl group called The Stilettos. It was at The Stilettos’ first gig in October 1973, at a small bar on 24th Street called the Bobern Tavern that Stein met Harry.

According to Gary Valentine, bassist for Blondie in their nascent ’75-77 period, Harry and Stein have a star-svengali relationship that drives the band dynamic. “Debbie was always fragile and Chris gave her support, but at the same time Chris is eccentric. We used to call them Ike and Tina,” says Valentine, now a London-based author who writes as Gary Lachman. “When the band got back together in 1997, by which point Chris and Debbie were no longer a couple, I visited Chris in his loft in Tribeca. It was like Mick Jagger’s apartment in Performance. The place was a wreck. Debbie would come over each day to clean up and do his laundry.”

“Did I want to manage her, be in a band with her, go to bed with her? All of the above,” says Stein, with a shrug. “I thought Debbie was smashing, and what can you say? She is what she is.”

“The Stilettos was a theatrical kind of thing,” says Harry, pointedly not reacting to Stein’s comments. “It was on the fringes of the drag scene, very gay, with each girl having a persona and specialising in her own musical area. A playwright called Tony Ingrassia took over and made us sing the same thing over and over again until we got to what he called ‘the core’. It turned out to be very good training but we hated it at the time.”

Stein became guitarist for The Stilettos, but the band split when Ingrassia, stung by terrible reviews for a play he wrote about Marilyn Monroe called Fame, fled to Berlin. Stein and Harry, now part of a hip downtown milieu, moved into a one-bedroom apartment in Little Italy. They claim they didn’t have much in the way of long-term ambition – “We were artists, dreamers, pie in the sky,” says Harry – but a single, seemingly insignificant event shaped their future fate as pop stars.

“We played at Max’s and CBGB with The Stilettos,” Stein says, “and there was a transitional period where we were trying out different things and playing under different names. For the whole time, Debbie had short brown hair. Then she came home one day with her hair dyed blonde. That was it from then on.”

THE FIRST THING TO DO WAS yo get a new band together. People came and went. The guitarists Ivan Krall and Fred Smith left soon after they arrived, the first to play with Patti Smith’s group and the second to join Television as bassist. Harry and Stein put an advertisement for a drummer in the Village Voice. Fifty people turned up. The fiftieth was Clem Burke. “He was just a kid of 18 but he was already very rock’n’roll, with platform boots and long Keith Richards hair,” says Harry. “He knew what it was all about and he knew who we were, which impressed us. He was living it, even then.”

“Rock’n’roll was manifest destiny for me,” Burke confirms, down the line from Los Angeles. “Chris and Debbie were from an arty scene but I had grown up on the Top 40 – Sinatra to the Stones to The Standells – and my chief interest was in being a pop star. Our common ground was the New York Dolls.”

Bassist Gary Valentine and keyboard player Jimmy Destri were part of Clem Burke’s contingent from New Jersey. “Gary could hardly play,” says Stein. “He had only just picked up the bass. But he was so good-looking and charismatic that it was a no-brainer.”

Bassist Gary Valentine and keyboard player Jimmy Destri were part of Clem Burke’s contingent from New Jersey. “Gary could hardly play,” says Stein. “He had only just picked up the bass. But he was so good-looking and charismatic that it was a no-brainer.”

While Destri was an accomplished musician and songwriter, Gary Valentine was a directionless 18-year-old living in a Lower East Side storefront, having been kicked out by his parents after coming home past midnight one time too many. He had also got his 17-year-old girlfriend pregnant and been given a statutory rape charge as a result. The experience inspired the early Blondie song Sex Offender, later changed to X Offender with new Debbie Harry lyrics about a prostitute who falls in love with the policeman who arrests her.

“Chris and Debbie had been on the scene for a while,” says Valentine, who recalls jamming on Stones songs for his audition.

“Chris’s parents were Reds, Debbie was into that gay fringe theatre thing, but Clem and I were just kids who had grown up on the Beatles invasion. We brought in the ’60s pop sound and soon we all started wearing skinny ties and suits. We reinvented ourselves.”

The band settled into the now infamous Blondie loft on the Bowery, a block from William Burroughs’ apartment in one direction and CBGB in the other. Nobody had any money – Harry worked in a belt-buckle factory, Stein sold a bit of pot – and in 1975 New York City itself was bankrupt. After President Gerald Ford denied a request for a bailout, The Daily News ran the headline: Ford To City: Drop Dead. Much of Lower Manhattan was a no-go area. Gary Valentine remembers Alphabet City in The East Village as a place you went “for heroin, a cut price hooker, or to get beaten up”. An incident outside the Blondie loft that winter indicated just how desperate times were.

“Someone came in and shouted: ‘There’s a frozen dead guy on the street!'” remembers Chris Stein. “Everybody ran outside and sure enough, this derelict was dead. We all paused in supplication and horror. And the incredible thing was, someone had stolen the dead guy’s shoes. We had seen him earlier in the day and he definitely still had them on. This is the same Bowery that’s now lined with boutiques and expensive hotels. We found this rotting city evocative and glamorous, but it couldn’t stay that way.”

“We all felt, very strongly, that New York was a different country,” sats Harry. “It wasn’t like the United States. It did not embody the American spirit and that’s what made it so unique and wonderful. People who were brave enough to come here made it their own.”

The place with the greatest potential for freedom of expression was CBGB. Now due to be immortalised in a movie of the same name, the club, run by Hilly Kristal that became the birthplace of New York punk was, according to Stein, “really grim. There was a long abandoned kitchen behind the stage that was covered in grease and with hamburgers left there, uncooked, for 10 years. And Hilly had these two dogs, long skinny things that used to shit everywhere.”

“Before CBGB’s we were at Max’s the whole time,” says Harry. “One night Elda [Gentile, former Stiletto] turned up and said: ‘I just saw these guys play in a bar downtown, and they were dressed like old men.’ That was Television.”

So began Blondie’s time in one of the most fascinating and mythologised periods in the history of music. The band endured a fair bit of snobbery from the ultra-cool CBGB crowd during their sets at the club in the winter of ’75. Television were kings, Patti Smith was head girl, The Ramones were the jokers in the pack, and Blondie were the runts of the litter, third on the bill and laughably inept. A long held rumour has it that Smith tried to freeze Harry out of the scene. “I don’t know if she was unwelcoming…” says Harry, hedging her way through the only frosty moment of our conversation. “I can’t explain for her… you would have to ask her… Maybe she just didn’t really like what I was doing. Certainly we all love her, there’s no doubt about that.”

“Of course there was a rivalry between Patti Smith and Debbie Harry,” says Gary Valentine. “Patti would turn up to our gigs at CBGB, hanging out at the back with a little mafia based around [Television’s manager] Terry Ork and make snide remarks throughout our set.”

After rehearsing incessantly through early ’76 in the Blondie loft, and finding the missing link between ’60s girl group innocence, punk provocation and trash culture, Blondie release their debut album in December. They toured the UK with Television that year and it was at the first UK gig, at Friars in Aylesbury, when they realised they might be onto something. “Up until then we had only been playing in New York where everyone was a cool  beatnik and nobody showed any enthusiasm whatsoever,” Stein recalls. “But from the moment we went on stage at Friars the audience went crazy. We had never seen anything like it. At the same time everyone came down hard on Television. They had a song called Prove It. The audience kept shouting, ‘Prove it!’ Tony Parsons wrote a glowing review of our show. That was the beginning of Blondie as a big band and the first time anyone had said anything nice about us.”

beatnik and nobody showed any enthusiasm whatsoever,” Stein recalls. “But from the moment we went on stage at Friars the audience went crazy. We had never seen anything like it. At the same time everyone came down hard on Television. They had a song called Prove It. The audience kept shouting, ‘Prove it!’ Tony Parsons wrote a glowing review of our show. That was the beginning of Blondie as a big band and the first time anyone had said anything nice about us.”

IT WAS ALSO THE START OF BLONDIE THE ICON: STYLE queen, sex object and coolest girl in town. In the early days image manipulation was pre-meditated, with Harry posing for Creem magazine’s “Creem Dreem” centrefold, in zebra print playsuit and animal tooth necklace (see page 47). Then it went out of control.

“That was Chris’s underhand propaganda method,” says Harry, pointing sideways at her former boyfriend. “He would take loads of pictures of me and put them out all over the place. What happened was this. We worked very hard for seven or eight years. We knew we were a pop band, and we knew I had this little-girl-woman-sex object thing. And then, in 1981, we stopped cold and took a year out. In that interim, in that absentia, there was this thing that happened, which was shocking to me. It grew uncontrollably without any of us doing anything, and suddenly it was Blondie the icon, and I thought: Is this me they’re talking about?”

Blondie’s success grew wildly beyond what anyone in CBGB could have expected. After the Australian pop TV presenter Molly Meldrum mistakenly played the video to In The Flesh, the pretty B-side to the rather less commercial X Offender in the summer of 1976, Blondie had their first hit. The floodgates opened.

Rip Her To Shreds, Debbie Harry’s bitchy message to “a conglomerate of girls on the scene at the time”, followed in November ’76. February 1978’s Denis, a gender-swapping cover of the 1963 doo-wap tune by Randy & The Rainbows, made way two months later for (I’m Always Touched By Your) Presence, Dear, Gary Valentine’s song about the telepathic way his girlfriend always seemed to call just when he had taken a pretty girl back to his hotel. Picture This, Hanging On The Telephone and Heart Of Glass, an attempt at emulating Kraftwerk that ended up as a disco classic in the meticulous hands of glam-era producer Mike Chapman, hit the charts in quick succession through 1978. May ’79’s Sunday Girl must be the only UK Number 1 about a cat, written by Stein to make Harry feel better after her (male) kitten ran away when they were on tour. In September 1979, Dreaming ripped off Abba’s Dancing Queen without anyone noticing. It was an astonishing run, a string of hits that added up to record sales of over 40 million and a series of sell-out tours, and ended with the band heavily in debt until they reformed in 1997.

“If I was going to fault any aspect of how we handled our success, it would be our lack of foresight,” says Chris Stein today, “We never thought about the future.”

AS BLONDIE’S STAR ROSE SO DID THE push and pull within the band, a situation allegedly exacerbated by  Peter Leeds, Blondie’s manager from 1977 to 1979. Leeds took what Harry calls a divide-and-conquer approach to band management. Gary Valentine was the first to go, to be replaced by the English musician Nigel Harrison.

Peter Leeds, Blondie’s manager from 1977 to 1979. Leeds took what Harry calls a divide-and-conquer approach to band management. Gary Valentine was the first to go, to be replaced by the English musician Nigel Harrison.

“I never wanted [Leeds],” says Valentine. “[When] he brought out contracts, I told him I wanted to show it to a lawyer before I signed and from then on he had me pegged as a ‘troublemaker’.”

For the cover of Blondie’s breakthrough 1978 album Parallel Lines, the band were shot by former CBGB door girl Roberta Bayley. Each band member picked the photograph they liked best of themselves. Leeds replaced them with photographs of the men smiling and Harry frowning. “He did that because he was mad at me,” Harry explains. “He wanted me to dump the band and become a solo artist and I wasn’t having it.”

On a flight from Japan in 1978, Leeds concluded an argument with Chris Stein by telling him he could be replaced. “Oh, he did that all the time,” says Harry. “He told me that I could be replaced. With who, he didn’t indicate.”

Recollections differ. “Peter Leeds only ever chaperoned and encouraged is and I don’t recall him ever saying I could be replaced,” says Clem Burke. “He just became one of the things that went pear-shaped with this band.”

“In terms of the way we got on, we weren’t worse than anyone else, The Ramones didn’t talk to each other for years,” says Stein, citing perhaps the most famously dysfunctional band in the history of rock’n’roll. With an air of resignation, Debbie Harry adds: “It’s very hard to keep a band together. In theatre and film there is the director from which everyone branches off, but unless you’re James Brown it’s not like that in a band. We didn’t want to be dictators. We wanted it to be that everyone had a say, or an opinion at least… then we’d have to kill them.”

Meanwhile, Harry and Stein were pursuing new interests, causing further friction with their punk peers. A friendship with the New York graffiti artist Fab 5 Freddy led to an introduction to the city’s young hip hop scene, and Harry’s game-changing rap on January 1981’s Chic-influenced 7-inch, Rapture. “Freddy took us to this huge, super-exciting event in the Bronx,” recalls Harry. It was in police athletic grounds; a mini festival in which Grandmaster Flash would be up one moment and some no-name from the audience the next, doing their thing. We were the only white people there. Freddy was wearing a fedora and all these kids in stocking caps were pointing at him shouting, ‘Look at that church nigger!’ They thought we were Kool & The Gang.”

The Ramones were quick to point the finger at Blondie as disco-dancing sell-outs, but as Stein says: “I was listening to all kinds of music. We loved Donna Summer and we loved Giorgio Moroder, which led to Call Me. We admired Bowie and the Stones; people who changed their style.”

Stein renewed his links to the downtown art scene in 1979 with TV Party, an anarchic cable television show he co-hosted with former Warhol Factory regular Glenn O’Brien. A few months later, Blondie’s acceptance into the mainstream was sealed when Debbie Harry became an honorary Frog Scout on a 1980 episode of The Muppet Show. It was also around this time when the band’s regular joint smoking gave way to cocaine use, which then led to heroin.

“After Vietnam, all the soldiers came back with drugs and it became big business,” explains Harry. “First it was pot, and by the end of the ’70s it was a case of ‘Say hello to my little friend,’ with cocaine everywhere you went. Later on, when it was all going wrong and we got desperate, hard drugs became a form of pain medication.”

“Yeah, but we also love William Burroughs and Lou Reed,” says Stein, “and being a junkie was the way to go. What we didn’t know is that when you become a junkie everybody flees. It was fine to do tons of cocaine but the moment you do heroin, Goodbye.”

Blondie’s decline was as rapid as their rise. Guitarist/bassist Frank Infante sued the band for lack of involvement on 1980’s platinum-selling Autoamerican. When the band took a year-long break in 1981 Debbie Harry released KooKoo, a self-consciously arty take on funk produced by Chic’s Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards, while Jimmy Destri made Heart On A Wall, a forgettable piece of slick new wave that further depleted Blondie’s energy as a functioning group. 1982’s The Hunter, the final set until Blondie’s 1999 reunion piece No Exit, was the sound of a band running out of ideas, not least because it coincided with Stein and Harry’s descent into heroin addiction.

By 1983, Chris Stein was falling apart in other ways. Large red welts were appearing all over his body, the symptoms, it turned out, of a rare autoimmune condition called pemphigus vulgaris. It called a halt on Blondie as Harry, also fighting to get off heroin, gave up her career to look after Stein. “This thing was supposedly genetic,” says Stein, “but I knew I had compromised my immune system by getting stoned so much and working so hard. I missed an entire winter. In a way it was an adventure because I was hallucinating like crazy.”

“It was off the wall terrifying,” counters Harry. “He was completely emaciated. Aids was happening, we had no idea what this thing was.”

Worse was to come. Harry and Stein discovered that the revenue from the hit albums, smash singles and sell-out world tours wasn’t heading in their direction. Where did all the money go? “It wasn’t Peter Leeds,” says Stein, scotching long-held rumours. “For the two years we made the most money our accountant didn’t pay any fucking taxes!” Stein gets increasingly angry at the memory. “I wound up broke.” Stein owed the IRS a million dollars. He and Harry were forced to sell the smart uptown apartment they had bought when the band got big. “And I wasn’t making any money at all. Eventually they let me off with paying $500 a month for a very long time, right up until we got the band back together.”

“The same thing happened to me,” says Harry. “We got hooked up with the wrong people.”

“It’s a standard thing,” says Stein. “You’re playing Max’s Kansas City, you’re a kid, you’re writing songs and life is great. Everyone is very nice to you, they tell you that you can trust them, so what are you going to do? Are you going to wade through a lot of very complicated legal terminology or are you going to play the next gig?”

“If you’re going to be a successful artist you have to be a business person as well, and that’s a lesson we’ve both learned,” says Harry, looking resigned. “The problem is, neither of us are very interested in business.”

“I’m still not interested,” adds Stein, throwing his arms up.

“When I watch cop shows on TV I sometimes think: man, I wish I became a cop. That would be nice. But then you think of the 18-year-old you as a policeman – or a businessman. It was never going to happen.”

BLONDIE REUNITED IN 1997. Gary Valentine joined briefly, inspiring the bassist to claim he must be one of the only people to have been fired from the same band twice, while Frank Infante and Nigel Harrison attempted to sue when they didn’t get the call. Jimmy Destri wrote Maria, giving Blondie its first UK Number 1 since 1980’s The Tide Is High, before leaving in 2004 to get over his own addictions. Stein, Harry and Clem Burke kept going. And then there was Blondie’s induction into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland Ohio, in 2006.

“That was incredibly embarrassing,” says Stein. At the induction, Frank Infante, alongside Nigel Harrison, took the microphone to drunkenly plead with Harry to be able to join Blondie’s 2006 line-up on-stage. “I still have people asking me how much I paid Frankie to do that because everyone thought the Sex Pistols not turning up was going to be the big story and we managed to overshadow them. The crazy think is that if he wanted to play with us he could have called us, but on the night? I hadn’t spoken to the guy in over a decade.”

What remains, after all the emotional and financial pain, is a still-visible bond between Harry and Stein, separated since 1989 but still close, judging by the way they sit side by side beneath those Warhol prints in the terrace bar. How do they feel about Blondie today?

“After all that has happened…” reflects Debbie Harry, “it’s kind of great. It’s also a different world. Back in the day, touring was like the Wild West. We would ride into town and triumph or fail and you didn’t know what was going to happen. Now it’s all mapped out.”

“My feelings on Blondie is that it was all going according to plan and then something went wrong along the way,” says Clem Burke. “It still does. What happened with [underwhelming 2011 album] Panic Of Girls? At the end of the day we’re a rock’n’roll band and we need to recapture that again. We need to make Parallel Lines Mk II.”

“I made some hard choices,” says Debbie Harry, bringing two hours of memories to a close. “I made a lot of stupid decisions. But I had no expectations when I was a kid and I’ve had a great life. Chris and I have stuck by the core of who we are and what we can live with, emotionally and spiritually. What we’re left with, is peace of mind.”

What BLONDIE Did For Us.

Five ways in which Debbie Harry and co saved pop music, from Will Hodgkinson.

1. Brought disco zest to New York Punk

From the very beginning Blondie aimed to bring the good times, even as they inveigled themselves into the serious world of downtown art rock. Early sets include covers of dancefloor favourites Honey Bee and My Imagination, while Heart Of Glass, written in 1975, was the band’s first disco original. Cue frosty frowns from those black-clad CBGB regulars.

2. Gave us pop’s most influential frontwoman

From Madonna to Karen O to Lady Gaga, Debbie Harry’s ice-cool persona and impeccable style has influenced generations of singers. Suitably in awe, Shirley Manson of Garbage has called her “the most beautiful woman on Earth”.

3. Saved Chrysalis Records

The success of Plastic Letters and Parallel Lines revived the ailing British label’s fortunes in 1978. “They had Jethro Tull and not much else,” says Chris Stein. Chrysalis’s 1980s pop-streak – Billy Idol, Pat Benatar, Two-Tone Records etc – couldn’t have existed without Blondie.

4. Set the look for indie bands

The boys in Blondie started the suits-Converse-skinny ties look since used by The Strokes, Franz Ferdinand and many others. Debbie’s classic outfits are myriad, but that bottle-blonde dye job – not quite reaching the back of the head – nails indie glamour.

5. Brought hip hop to white audiences

Five years before Run-D.M.C.’s take on Aerosmith’s Walk This Way, Blondie’s Rapture (1981), namechecked Grandmaster Flash and Fab 5 Freddy after a trip to a Bronx hip hop show. Debbie made up her rap – in which the man from Mars eats cars, bars and guitars – on the spot, in the studio.

Catch Blondie on their summer tour. For dates, info and tickets visit blondie.net