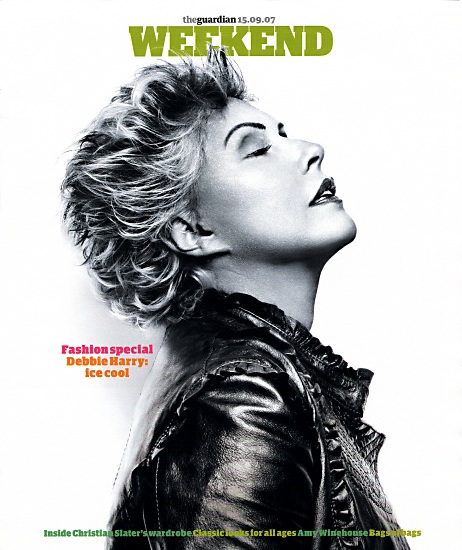

theguardian WEEKEND magazine

Fashion Special

Debbie Harry:

ice cool

Pages 3, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

Page 3

WHAT’S INSIDE

Debbie Harry

What’s my secret? Bowing out at the height of my fame and coming back 15 years later as a ready-made legend. That and fantastic cheekbones. Sure, there are regrets. Men are scared of me and I don’t have any kids. But, hey, you can rent ’em these days.

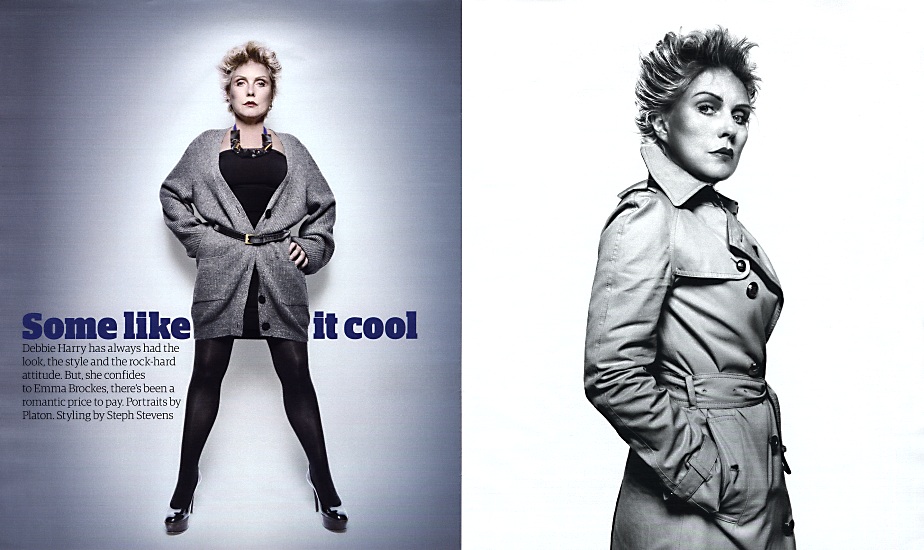

Some like it cool

Debbie Harry has always had the look, the style and the rock-hard attitude. But, she confides to Emma Brockes, there’s been a romantic price to pay. Portraits by Platon. Styling by Steph Stevens.

Debbie Harry, who was always too beautiful for punk, was an “ugly kid”, she says, right up to the point when she turned 16 and it suddenly all came together for her. “I had the chubby phase. I never had good hair. I dressed like a ragamuffin tomboy. I wasn’t a girly girl.” At 63 she is as pouting and pale as uncooked bread, her demeanour as cool as it ever was. “I like to look good and feel good in what I’m wearing, but I don’t like to super-fuss. What do they call that?” She smiles vaguely. “I’m not a real high-maintenance person.”

We’re in lower Manhattan, in one of those neighbourhoods where everyone pretends they’re being secretly filmed by MTV, although the real stars still stand out. (It’s a question of discipline: the wannabes keep sneaking looks to see who’s watching them.) Harry crosses the photographer’s studio in towelling sweats and huge, blackshades, her head fixed forward to repel anyone with ideas of approaching her, and dragging a small, neat suitcase containing beauty gear. “Thank God for wheelie bags!” she exhales, and explains that she prefers to do her own make-up, unless she’s being shot for Vogue, in which case the “responsibility” to look good has to rest on someone else’s shoulders.

The extent to which style in the late 70s and 80s, and those echoes of it still around today, have to do with the  individual wardrobe choices of Deborah Ann Harry of Hawthorne, New Jersey, is something that bemuses her. It’s an attitude as much as an image; if you go back to the early Blondie videos, they still look strikingly modern – Harry out front, smiling garishly, as if she knows something about the audience that they haven’t yet quite admitted to themselves and doing a languid, ironic dance that has never gone out of fashion.

individual wardrobe choices of Deborah Ann Harry of Hawthorne, New Jersey, is something that bemuses her. It’s an attitude as much as an image; if you go back to the early Blondie videos, they still look strikingly modern – Harry out front, smiling garishly, as if she knows something about the audience that they haven’t yet quite admitted to themselves and doing a languid, ironic dance that has never gone out of fashion.

For these reasons, large numbers of people still wander about in Blondie T-shirts, and you recognise the broader influence when you see it: the square hair, the wide belts, the glittery eyes and heavy rouge (without the advantages of Harry’s bone structure, people do what they can with war paint); in short, the combination of sophistication and guilelessness that all women over the age of 18 should apparently be striving for.

Harry says it’s a longevity helped by absence; in 1982, at the height of the band’s popularity, Blondie disbanded when Chris Stein, the guitarist, fell seriously ill and Harry, his then girlfriend, resigned to look after him. The band didn’t work together again until 1997. “In a way it was providential – it went in our favour because people were copying us and there was nothing I could do about it, and then when we came back we had taken on this status as being something legendary, or some ridiculous thing. By then I just felt flattered by it. It’s interesting to see what becomes style and what becomes acceptable.”

At 63 she looks remarkably unchanged, which, again, may be a mark of attitude as much as actual image: Harry has a childlike inability to concentrate and, as the stylist tries to do up her buttons, keeps absent-mindedly wandering off. She’s professional though: on time to the minute and so business-like about the photoshoot that – almost unheard of, this, for someone of her celebrity – it finishes early.

A few years back, people started taking Harry aside and delicately suggesting that a woman of her age might want to start making different choices. “It was in the 90s,” she says, “when we brought Blondie back and I was  much heavier than I am now and I wanted to do something that was ‘today’ yet reminiscent of the past – identifiable as a Blondie thing. And I couldn’t quite get it together. I do remember different people saying to me, you should try to dress more your age. I agree – to a certain extent. I feel like I don’t really look good in clothes I looked good in in the 80s. Styles have changed, of course, but I’m not a little girl and I dressed more like a little girl then. I’m a lay-dee…” She grins. “God.”

much heavier than I am now and I wanted to do something that was ‘today’ yet reminiscent of the past – identifiable as a Blondie thing. And I couldn’t quite get it together. I do remember different people saying to me, you should try to dress more your age. I agree – to a certain extent. I feel like I don’t really look good in clothes I looked good in in the 80s. Styles have changed, of course, but I’m not a little girl and I dressed more like a little girl then. I’m a lay-dee…” She grins. “God.”

(She doesn’t have a problem with fashion magazines touching up photos, by the way. “I think the more they touch it up the better. Smooth that one out!”)

Her new album, Necessary Evil, is for grown-ups. She wrote it herself and it was a much leaner recording process than making a Blondie record; she enjoyed not having to negotiate with the other band members. One of her favourite lines is from the title track, about a cheating scumbag she can’t help going back to. “Nerves on the edge/Necessary evil/Powder in a keg/Necessary evil/You come you go/Oh yes, oh no.” It’s the ambivalence of falling for someone unworthy and, in classic Debbie Harry style, oscillates between innocence and cynicism: “The secret ingredient is the knife in the cake,” she sings.

“I don’t know if I would use the word cynical. It’s sort of more… dark humour, I guess. I guess more sophisticated. It’s not a kids’ record. Some of them might get it – who knows. Age is such a different thing these days.”

Harry grew up in a suburb of New Jersey in a conventional, church-going family of modest means. Shopping trips were a nightmare; she wanted to wear only black. Her mother wasn’t having it. Looking back, Harry says, she thinks her mother secretly had quite a good eye. “We always had terrific rows about what to wear. I appreciate some of the things she said now; she had some good fundamental rules that she followed. I wanted radical, I wanted sex, I wanted movie stars. But she had very classic ideas and she was right in many respects – that some things would ultimately look better on me; like a tailored line, a simple line, would look better on me than something frilly. I mean, they didn’t have any money, she didn’t have a great wardrobe or anything; a few pieces.”

When she was 19, Harry came to the city with no firmer idea of what she might do than hang out, being cool, in the Village. And that’s largely what she did. She made ends meet by waitressing and played in two other bands before Blondie was formed. The early years in New York taught her “humility”, she says. “It’s good to be a small fish in a big pond.” And then, with the release of the album Parallel Lines in 1978, she was suddenly famous, at a  time when it was still relatively unusual for a woman to front a rock band.

time when it was still relatively unusual for a woman to front a rock band.

Harry felt a freedom to express herself on stage that she didn’t feel in real life. “I think one thing that’s interesting about rock’n’roll is that sexuality is a little more ambiguous. Mick Jagger was very fey and I always liked that. I think that women who get up on stage in rock are manly in lots of ways – a certain ferocity. I’m not afraid to be blunt. A lot of women are more decorous. They hold back. They’re more feminine. It’s easier that way.” She looks a bit crestfallen, and I ask if she thinks she has suffered, romantically at least, for that attitude. “I don’t know any more and it’s too late for me to do anything else. It really is. It’s too late. I can’t go back.”

Harry sounds so regretful that I’m a bit thrown. What would she have done differently? “Well, because I’ve been doing what I’ve been doing for so long, I don’t know. In terms of being quieter and letting somebody else take the lead? That’s the thing: men like to take the lead. I don’t mind a man taking the lead, but I’m used to doing things. So it takes a person who is very sure of himself, very comfortable, not offended and not uptight. Men are so fragile in that area. About power. It’s funny.”

Harry lives alone. “I’m single. I date. I don’t like to call it dating, actually. I have nice times with good friends.” She grins. “I do have a lot of good friends.” And if men are afraid to ask her out, she says, “if only they knew what a mushnik I am! It makes me laugh and it teaches me a lesson. When I meet people who I admire and who are really famous, I’m [intimidated] just like that. And then I think: oh God, I see people responding to me like that. It’s not the way to go, not the way to handle it.”

Her parents were surprised by her success and nonplussed by her music. She flew them to Chicago once, to see her perform, but it didn’t work out. “It was too loud for them, too abrasive, and the subject matter didn’t make any sense to them.” She has worried in the past that her fame exposes them to sides of life from which they are otherwise protected: mad fan mail, stalkers outside their home. “There was one particularly horrifying letter all about money – he was in prison, waiting to get out. I thought: oh my God, it’s like In Cold Blood. I told them never to talk to anyone.”

If she was starting her career now, she says, it would be much harder to find her own voice. To her shame, she watches the TV show American Idol and enjoys its meanness, but hates what it says about the music industry. “It’s not unique in any way. It’s grinding out more stuff, it’s not encouraging people to come on and play their own music. It’s just karaoke. And that to me is nothing. I can go down to any bar in the East Village practically any  night of the weeks and see some asshole standing up there singing Stairway To Heaven.”

night of the weeks and see some asshole standing up there singing Stairway To Heaven.”

At times it’s been hard for Harry not to get bored herself, given how eager people are for her to stay the same, to be the person she was when they were young and Blondie was their favourite band. “I think that’s partly why I did this album. To express myself. To be part of today. To be exactly who I am at this moment, not who I was 30 years ago, pretending. Doing too many Blondie shows makes me bilious; and audiences get stuck.”

When she hit 60, she felt the beginnings of an age-related crisis, but worked hard to resist it. She counted her blessings – her health, her interesting life – and told herself, unceremoniously, to “shut up. Shut up about it. You get your priorities straight by then. You’re forced to.”

She doesn’t have children. “I rent kids,” she laughs. “I know lots of people who have children that I dabble in.”

Was that a conscious decision, not to have any? She clears her throat. “I did consciously decide that. At the time our lives were very tempestuous and I really didn’t have time or – I don’t know, I think I was so much of a child myself. Now that I’m comfortable with myself, I would like to, I would like to have some. But I haven’t done it yet. I don’t know exactly how I would do it – whether I would adopt children – but I have been thinking about it.”

What, she’d go the Angelina Jolie route? “I don’t know. She obviously… I mean she must have a couple of nannies helping her. She couldn’t possibly do it single-handed, and for me that’s a lot to consider. There’s probably some kids that I could really help, though.”

In terms of politics, Harry is a Democrat and admires Hillary Clinton more than – “what’s his name, Osama? Obama, is it?” – who she thinks is too slick.

“I think it’s a shame what happened to Hillary’s husband. I never felt that what he’d done was a great, terrible thing, except that he should’ve come out with it right away and said: fuck it, man. I like the fact that she has a lot of experience and she’s really smart, she thinks on her feet. The only thing I don’t like about her is that when she’s sitting there on these panel discussions and someone else is speaking, she always nods in agreement. There she is, nodding away; it makes her look like a lady wrestler or something. Hillary, the nodding’s got to go.”

Earlier this year, Harry did a live duet in New York with Lily Allen – “she’s cure” – and wants to know if “Amy Winehouse is really going to rehab? Her voice is so cool.” She’s spending the rest of the summer on “enforced vacation”, waiting nervously for reviews of the album to come out, “going to the gym, swimming, and…” she casts about for other things she’s been doing. She shrugs. “I bought a hose rack.”

Harry used to campaign to be called Deborah, to show how mature she’d grown, but she doesn’t really care these days. “I don’t think it matters.” She zones out for a beat and zones in again. “I don’t know whether I’ll start another band. There’s one already called Dirty Harry, I think, so I can’t use that any more. I don’t know. Maybe I’ll just call it the Evil Band. The Evil Beatles.” She looks delighted by this and giggles again, surveying the room in general wonderment.

Page 18: Grey cashmere ribbed cardigan, £495, by Stella McCartnet, 30 Bruton Street, London W1, 020-7518 3100. Black spandex tube dress, £22, American Apparel, 3-4 Carnaby Street, London W1, 020-7734 4477. Belt, £17, by Cos, Unit 1, 222 Regent Street, London W1, 020-7478 0400. Tights, £4.99, by Charnos, from tightsplease.co.uk. Patent platform shoes, £305, and PVC necklace, £355, both by Marni, 26 Sloane Street, London SW1, 020-7245 9520.

Page 19: Trench coat, £695, by Burberry, 21-23 New Bond Street, London W1, 0700 078 5676.

Page 21: Men’s shirt, £39, by Cos, as before. High-waisted skirt, £195, by Diane Von Furstenberg, from matchesfashion.com. Tights, £4.99, by Charnos, as before. Horseshoe ring, £95, by Tata-Naka, from brittique.com.