RHYTHM

Pages 1, 6, 7, 9, 10

Welcome

Hello and welcome to the Christmas issue of Rhythm. It’s a privilege to be here as Guest Editor. What I’ve tried to do in this issue is showcase two very talented and important drummers. One who has contributed immensely to the evolution of drumming and one who is just beginning to. Both Earl Palmer and Fab  Moretti have furthered the path of drumming for all of us. Mr Earl Palmer: what can I say? Sheer poetry in motion, the man has a positively smooth sense of style which he absolutely radiates when seated at his drums. I’ve been completely mesmerised over the years by watching – along with

Moretti have furthered the path of drumming for all of us. Mr Earl Palmer: what can I say? Sheer poetry in motion, the man has a positively smooth sense of style which he absolutely radiates when seated at his drums. I’ve been completely mesmerised over the years by watching – along with  other drummers such as Jim Keltner and Charlie Watts – Earl play his weekly residences at various jazz clubs around Los Angeles; every performance a virtual drum clinic. These gigs were also a life lesson for me and proved to show what a true gentleman Earl is. Much to his chagrin, I expect, Earl invented rock’n’roll drumming, and for that we all owe him a huge debt. Ladies and gentlemen, with much respect I give you Earl Palmer.

other drummers such as Jim Keltner and Charlie Watts – Earl play his weekly residences at various jazz clubs around Los Angeles; every performance a virtual drum clinic. These gigs were also a life lesson for me and proved to show what a true gentleman Earl is. Much to his chagrin, I expect, Earl invented rock’n’roll drumming, and for that we all owe him a huge debt. Ladies and gentlemen, with much respect I give you Earl Palmer.

Fab Moretti is the drummer in the best band I’ve seen in the last 10 years, The Strokes. Fab’s style and energy is a major contributor to The Strokes’ sound. He captures the spirit of what it’s like to be a team player in a band; think Ringo Starr, think Charlie Watts… Fab, along with his band is making a major contribution in changing the state of pop for the better. A great drummer and also a really nice kid, please welcome Fab Moretti.

Fab Moretti is the drummer in the best band I’ve seen in the last 10 years, The Strokes. Fab’s style and energy is a major contributor to The Strokes’ sound. He captures the spirit of what it’s like to be a team player in a band; think Ringo Starr, think Charlie Watts… Fab, along with his band is making a major contribution in changing the state of pop for the better. A great drummer and also a really nice kid, please welcome Fab Moretti.

Thanks to bands like Fab’s there’s a resurgence on the scene for real musicians, real bands, real artists. It seems that drums and guitars are back, so remember to support your local music scene and keep music alive.

In closing, I’d like to thank those of you who have supported my band, Blondie, over the years and I hope you enjoy our new disc, The Curse Of Blondie. Enjoy the issue; see you all soon…

Peace, love + Rock n Roll!

Clem Burke – 2003

Guest Editor, Rhythm

WHAT OUR GUEST EDITOR HAS BEEN TAPPING HIS TOES TO THIS MONTH…

CLEM BURKE, GUEST EDITOR

“I’ve been listening to a lot of Miles Davis: the complete Bitches Brew session is a great collection. Speaking of Miles, his keyboard player Herbie Hancock’s soundtrack to the film Blow Up is a constant source of inspiration with Tony Williams on drums. I’m also into Mars Volta’s De Loused In The Comatorium, and of course The Strokes’ Room On Fire. Also Bob Marley’s Legend, and The Who, Live at Leeds – the deluxe edition.”

Page 16

Page 16

Classic Track

We talk to the drummers behind some of the greatest music ever recorded…

THE TRACK ‘CALL ME’ (1980)

THE ARTIST BLONDIE

THE DRUMMER CLEM BURKE

Where was the track recorded? Set the scene for us.

“The session was basically a one-off with the producer Giorgio Moroder for the film soundtrack to American Gigolo. We recorded it at the Record Plant, New York City.”

What were your impressions on hearing the track for the first time?

“It was the first time I had played to an already sequenced basic track, consisting of a synth with a click track. The basic track was cut with the three os us: guitarist Frank Infante, bassist Nigel Harrison and myself playing along to the synth and click.”

How did you approach the track. What made you play the part you did?

“The drum intro was overdubbed later on, as well as the 16th note hi-hat groove. We basically thrashed out a sort of new wave boogie.

“The track was originally called ‘The Man Machine’. The demo consisted of different lyrics, along with a basic framework of the song. We had screened a rough cut of the movie and Debbie came up with the new lyrics that became ‘Call Me’. It’s funny, after the session we basically forgot about the song and went on a lengthy world tour. It was only after getting back I happened to turn on the radio in the limo from the airport, and heard something that sounded vaguely familiar. ‘Call Me’ was our next US number one.”

What set-up were you using?

“I was using one of my Red Sparkle Premier Resonator kits on the session. I went up to the Premier factory in Leicester and scrounged around until I found some Red Sparkle wrap that was left over from the ’60s; that’s what was used on the kit. I think it’s the same stuff they used on Keith Moon’s red kit. The drums were a 24″ bass, 15″ rack, 16″ and 18″ floors and 14″x5½” chrome snare, with my basic set-up of zildjian K cymbals.”

Which recording are you yourself most proud of?

“Of all the tracks I’ve played on, I’m probably most proud of the Blondie track ‘Rapture’, ‘Missionary Man’ by the Eurythmics, the Plimsouls’ ‘Playing With Jack’ and maybe the first Blondie single, ‘X-Offender’. That’s particularly near and dear to me because it was our first recording.”

Interview: Louise King

Page 23

Page 23

EVENTS DIARY

WHAT’S GOING ON…

Blondie

Well, of course, this is the ‘must see’ gig of the year! As we’re sure our Guest Editor Clem Burke would agree. See our New York heroes at: Glasgow Carling Academy (19 November), Nottingham Royal Centre (21), Newcastle City Hall (22), Preston Guildhall (23), London Shepherd’s Bush Empire (25).

Pages 37, 38, 39, 41, 42, 43, 44

Pages 37, 38, 39, 41, 42, 43, 44

SNAPSHOT

#3

FAB MORETTI & CLEM BURKE

Pictured at The Maritime Hotel, New York on October 7 2003.

Ever-youthful Blondie drummer Clem Burke and boyish Strokes sticksman Fab Moretti have a lot in common. They’re both great players, they both have cool hair, they both found fame in New York bands (who made it big in Britain first). They’re also both connected to beautiful blondes – Clem is in a band with Debbie Harry, Fab is engaged to Drew Barrymore.

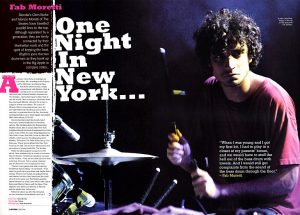

Fab Moretti – One Night In New York…

Fab Moretti – One Night In New York…

Interview: Clem Burke

Words: Jon Cohan

Photography: Rob Shanahan

Blondie’s Clem Burke and Fabrizio Moretti of The Strokes have travelled parallel lines to the top. Although separated by a generation, they are firmly connected by their Manhattan roots and the spirit of keeping the beat.

Rhythm joins the two drummers as they hook up in the Big Apple to compare notes…

As always, Clem Burke is looking lean and sharp. He’s standing in the hallway of The Maritime, an ultra-hip New York hotel where he has a 10pm appointment with Rhythm. Clem is joining us for a cover shoot and interview  with Fabrizio Moretti, drummer for The Strokes – the hottest band in New York, if not the world. Clem is staying in the hotel while his own band, Blondie, rehearse for a tour in support of their new album, The Curse Of Blondie. Fab is rehearsing across town. It’s the night before the Strokes go out on their own tour to promote Room On Fire, the much-anticipated follow-up to their hugely successful 2001 debut album, Is This It?.

with Fabrizio Moretti, drummer for The Strokes – the hottest band in New York, if not the world. Clem is staying in the hotel while his own band, Blondie, rehearse for a tour in support of their new album, The Curse Of Blondie. Fab is rehearsing across town. It’s the night before the Strokes go out on their own tour to promote Room On Fire, the much-anticipated follow-up to their hugely successful 2001 debut album, Is This It?.

Clem remembers that this trendy hotel was once a seedy flophouse for homeless sailors. The building skirts the Meatpacking District which, like so many other New York neighbourhoods has been transformed in recent years. In the 1990s, the same thing happened to New York’s Lower East Side, home to clubs like CBGB’s, which was the breeding ground for Blondie. Television, The Patti Smith Group, The Ramones. These bands defined the New York scene in the mid-’70s and have influenced a new generation of young bands like The Strokes.

While the photographer prepares for the shoot, Clem explains why he wants to interview Fab for Rhythm. “I find them inspiring,” he says of The Strokes. “They are the best band I’ve seen in the last 10 years. Fab is a great drummer and he deserves to be recognised for that.

While the photographer prepares for the shoot, Clem explains why he wants to interview Fab for Rhythm. “I find them inspiring,” he says of The Strokes. “They are the best band I’ve seen in the last 10 years. Fab is a great drummer and he deserves to be recognised for that.

“There’s a new generation that’s rejecting the Britney Spears thing,” he continues. “That wasn’t a good era in pop music and maybe that’s ending. These newer bands are going to bring out interest into older bands and the roots of rock in the same way The Beatles and the Stones showed us what came before with Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters and the blues. That might be why there’s an interest in Blondie and the whole New York scene.”

When Fab shows up after his rehearsal, the two drummers immediately bond as if they were old friends. Fab is clearly excited to be here.

“There’s this song on the new record that is totally, 100 percent influenced by ‘Rapture’,” he tells Clem. “Needless to say, you’ve influenced all of us.” After the shoot, we move downstairs to an outdoor lounge area to talk and take advantage of the unseasonably warm October night. The two drummers immediately plunge into conversation, but Rhythm occasionally manages to get a question in too…

Clem Bruke: So, Fab, how did you come to the drums?

Clem Bruke: So, Fab, how did you come to the drums?

Fab Moretti: “My brother’s three years older than me, so he was always feeding me music. One day he got a guitar. It was like a piece of art in the room that we shared. And he would play it and I would beat on stuff. My dad got me a snare and a bass drum. That was when I was 12 or 13.”

CB: So you’ve been playing for a good 10 years or so. Did you study at all?

FM: Yeah, I went to Turtle Bay music school. My mom would take me. I think it was on East 52nd St.”

CB: So what was an early influence for you? What record did you play along to on your bass and snare?

FM: “Believe it or not, Appetite For Destruction by Guns N’ Roses. Such a cool record.”

CB: That’s a great record and Steven Adler is a great drummer. So Appetite For Destruction made a big impression on you?

FM: “Yeah, because it was at a point where I had learnt what it meant to be defiant. It was like, ‘I’m listening to Guns N’ Roses! They curse and talk about sex and drugs!’ I was around 11. Then I started hanging around these boys (The Strokes). I’m the second youngest in the band, and two years age difference was a lot. Julian was two years older than me and he started feeding me some really good stuff – Velvet Underground with Moe Tucker, and (pointing to Clem) you guys, and Television.”

CB: When you got the bass and snare, what were they?

FM: “Tama. I think I might have had a rack tom there too. But it’s funny, because then it started to grow, and we started rehearsing and getting our songs together with more finite things that we were gonna play consistently…”

CB: This is with The Strokes?

FM: “Yeah. Well, I’ve never played with anyone other than Julian (Casablancas singer, guitarist) and Nick (Valensi, guitarist). So as we were jamming it was, ‘Well, none of our songs use this rack tom, so let me put that away. And I don’t really use this crash cymbal so let me throw that behind the back’, and it just got smaller and smaller. It grew at a certain point and then it regressed (laughs).”

CB: And then it was easier to get in the cab.

FM: “Exactly!”

CB: “Especially nowadays in New York without the Checker Cabs. Back when we were playing at CBGB’s, the Checker cab was like our van because they were so big. Debbie used to be a waitress on Wall Street and we were doing this gig and I was putting my stuff in the Checker Cab and I went to take my stuff out and I flipped the door open and a car came and it took the door right off the cab!”

FM: “When we were doing it we would scrape together 20 bucks for one of those U-Haul vans. I played many a gig with my ass as numb as hell from sitting on the floor of those vans! But as far as the size of my kit goes, I cheat because I use my one cymbal as a crash/ride.”

CB: When you listen to a song, do you find yourself listening to the rhythm and to the drums?

FM: “Oh, absolutely. Especially these past two days. Julian came up with this crazy new song and it needs a very reggae type of beginning. As much as I don’t play like I know it, I was trained with rudiments and stuff, so it was about figuring this stuff out. I was so rusty it’s ridiculous.”

CB: Do you practice much nowadays on your own?

FM: “Yeah, I’m actually investing in some V-drums. I have to get my place finished first before I can play there…”

CB: “That’s always a problem in New York too – making a racket when you’re in an apartment.”

FM: “Yeah, when I was young and I got my first kit, I had to play in a closet at my parents’ house and we would have to stuff the hell out of the bass drum with towels, and I would still get complaints from the sound of the bass drum through the floor.”

CB: “You ever play on pillows and things like that?”

FM: “Oh yeah! And textbooks. They were a big thing in high school. The bounce-back is so good.”

CB: So The Strokes are essentially your first band? What a great group to have as a first band.

FM: “Well, thanks. I gotta stress that I don’t even think of myself as a drummer. I love drums with all my heart, but when it comes to projecting some kind of drum part, it has to do with everything that’s going on, and how they think of me and how I think of them. If I’m doing anything that might take away from any part, I feel like I’m actually doing harm to the song.”

CB: Let’s talk about the early days. How long did it take you from the inception of the band until you got signed? I know you did that demo that turned out to be an EP for Rough Trade. How long did that take?

FM: “Well, we started when Albert (Hammond Jr, guitarist) came in. He lived in LA pretty much all his life, but he knew Julian from boarding school and in 1998 he moved here to go to NYU, and that’s when the band got its final important element. From that till we were signed by Rough Trade was about two years.”

CB: “So you guys were doing a lot of club gigs around New York?”

FM: “Oh yeah, absolutely.”

CB: “What’s the first show you did out of town?”

FM: “It was in Atlantic City at this place called Max Dukes or Duke Max – something like that – and there was one person there to see us and it was Julian’s dad! (laughs). But we played our hearts out. I miss those days.”

CB: “But you have also opened for the Stones. Did you get to meet Charlie Watts?”

FM: “Yeah. He’s very nice, a really sweet guy, but he’s also pretty quiet and reserved. He does his own thing. One thing I noticed is, he never hits the snare when he hits his hi-hat.”

CB: “That’s a style a lot of people have picked up on, including myself. It seems so strange when you first see it, like he can’t hit simultaneously on the downbeat with the hi-hat and snare, but it’s such an effective groove.”

Rhythm: Both of you guys come from New York-based bands that have had a lot of hype attached to you by the media at an early stage in your careers. How did that affect you?

FM: “It’s like poker. We realised early in the game that you’re only gonna lose as much as you invest, as much as you put down, so we never really paid attention. I understand nowadays in the world we live in, music is less of an art form itself and more of a vein in entertainment. Out pop culture has gotten to the point where the music doesn’t matter that much. What’s good about being in a band who really don’t care about fame is that you don’t get sucked into that sort of blood source.”

CB: “Exactly. I asked Chris Stein and Debbie Harry for some questions they’d want to ask you, and Chris said if he was starting out today, he probably wouldn’t follow music as a career because it’s become too mainstream and not as important as it seemed to us when we were kids, so you kind of answered that question just now.”

FM: “That’s so true! When we set out doing this and there were actually people coming to our shows, we thought maybe we could set a blueprint of some kind. To understand what discipline is, understand what it means to have a goal and seek it out. Hopefully as bands, together we can help rejuvenate the heart and soul of it all.”

CB: “I think you guys have opened the door for a lot of other bands and can give people more of an appreciation for what the spirit of a rock’n’roll band really is…”

FM: “Thank you so much. That’s really nice of you to say.”

CB: So how does the recording process work for you? Do you and Nikolai (Fraiture, bassist) work separately on the bass and drum parts once you get the outline of the song?

FM: “There were three songs on the new record that were done live with all of us in the room together: ‘Under Control’, ‘You Talk Way Too Much’, and ‘Between Love And Hate’. The rest of them were done with just Nikolai and I together. When we get into the recording studio, there’s something really good about having a bassist and a drummer know that they’re laying down the foundation of the song.”

CB: Do you guys play to a click?

FM: “Yeah, a lot of times we do. I have the click in my headphones only and Nikolai doesn’t hear it. I was gonna ask you: once you guys lay down the bass, drums and one guitar, do the bass and guitar overdub stuff?”

CB: “Yeah, they drop stuff in and out. Back in the old days…”

FM: “… would you play in isolated rooms?”

CB: “We’d isolate the amps, but we’d be in the same room.”

FM: “Yeah, that’s what I mean. What we do is Nikolai and I play in the same room with the drums and the bass amp.”

CB: “So you’re getting some of the bass ambience in the drum mics?”

FM: “Exactly. We like that.”

CB: “Let it bleed…”

Rhythm: There’s currently been a lot of press comparing The Strokes’ sound to earlier bands, Blondie being one of them.

FM: “It’s an honour to is, really. (To Clem) Thank you, by the way. Not that I’m copying you, but just so you know that listening to your drums parts has been very influential.”

CB: “Well, I’ve got some influences from you now, from listening to the last Strokes record.”

FM: “That is too cool!”

CB: “That’s what music is about – you feed off one another…”

FM: “Like art.”

CB: “Exactly, like art. It’s about taking something and making it your own.”

FM: “I don’t hold myself up as a drummer. It’s awesome hanging out and doing a drum magazine photo shoot and interview, but more than anything I’m actually a slave to the music.”

CB: So what was the major difference between making the first album and making the second one?

FM: “I think it all boils down to experience, that’s all. The relationships are all the same, the love for music is all the same. We just had the upper hand on this record because we had gone through it once before.”

CB: You started off with a different producer, Nigel Goodrich, this time before going back to the same producer (Gordon Raphael) from your first record. How far along did it get before it stopped?

FM: “It wasn’t even like we stopped it. Both parties gave each other a trial period, just because we wanted to have fun. And we did have fun and he is really good at what he does, but when the trial period was over it was like, ‘Maybe in five years, when we’re a much more experienced band and we’re on your wavelength, we’ll be able to come and hang out and record an album’. But right now we still have a lot to learn about our own process.”

Rhythm: So it has to do with knowing the producer and being comfortable with them?

FM: “Yeah. Gordon met us at a point where we were sort of growing together. He’s such an open mind. He knows exactly what he’s doing because he’s experienced and a little older, but he’s willing to break all the boundaries. If the needle goes a little bit into the red, if it sounds good he doesn’t care.”

CB: “Well Julian’s voice certainly has that sound on the first record where it’s a little overloaded and sounds great.”

FM: “I cannot stress enough how cool it is to be interviewed and have a talk with musicians. You know when you meet someone and you say, ‘Hello, how are you doing?’, and you expect, ‘Very well, thank you, how are you?’. And with this, it’s like we’re already gotten that out of the way, let’s talk about what’s real.”

CB: “I think it’s because drummers have a community, kind of simpatico thing going on too. There seems to be a community and brotherhood amongst drummers that perhaps isn’t shared by players of other sorts.”

FM: “You know why? Because we’re focused on knowing that we sit relatively in the back and we hold the foundation of the song. There isn’t much ego at play there.”

CB: Debbie wanted me to ask you, do you like pedicures?

FM: “I should get one (laughs)…”

CB: What’s the weirdest gig you played or the weirdest band you’ve ever opened for? Some bill that was totally incongruous? I’m thinking like with Blondie we opened for Rush, we opened for REO Speedwagon…s

FM: “The band Doves. Even though they’re great guys and really nice people, their audience was not liking us. We did a tour with them right at the beginning of it all.”

CB: So what’s the best shoes to wear when you’re drumming?

FM: “Converse. It’s like you’re barefoot on the drum kit.”

CB: Thanks for your time.

FM: “I just want to say this is pretty much the coolest interview I’ve ever done in my life. I’ve been having these interviews where they’ve been asking us the stalest questions. And here we’re having the greatest conversation and it’s just so cool…”

Clem Burke

East Coast

Confidential

The years 1977-82 were a Golden Age in popular music. As punk gave way to new wave, the UK hit parade was stuffed with catchy, controversial classics by home-grown artists. But one American band managed to dominate our charts and our hearts. They were Blondie. And 20 years on, their drummer Clem Burke is still one of the finest ambassadors for our art form.

Words: Jon Cohan

Photography: Robert Mathew, Alex Solca, Redferns.

Considering the fact that he had his first hit record some 25 years ago, Clem Burke appears surprisingly youthful as he talks about the rehearsal he had with his bandmates in Blondie earlier in the day. Maybe it’s the boyish  face and the full head of hair that helps to make him appear 10 years younger than he really is, but something must be said for the rejuvenating power of rock’n’roll drumming, an art that Burke has practised with full abandon and mighty conviction since he was a teenager growing up in New Jersey in the 1960s.

face and the full head of hair that helps to make him appear 10 years younger than he really is, but something must be said for the rejuvenating power of rock’n’roll drumming, an art that Burke has practised with full abandon and mighty conviction since he was a teenager growing up in New Jersey in the 1960s.

Clem Burke could certainly qualify for drum icon if all he had ever done was to play on the seminal power-pop classics Blondie recorded between 1976 and 1982, but Clem has never been one to rest on his laurels. His love and enthusiasm for music has taken him around the world, and his talent and virtuosity has landed him on some of the most coveted drum chairs in the business. Besides the ground-breaking grooves he created with Blondie, the band he helped form in New York’s Lower East Side in the mid-’70s, Clem has also recorded and performed with the likes of Bob Dylan, Iggy Pop, Eurythmics, Pete Townshend, The Ramones, Joan Jett and many others. In the last year alone he has worked with such disparate artists as Nancy Sinatra and The Romantics.

Tonight he is the willing subject of Rhythm’s questions, himself having interviewed Strokes drummer Fab Moretti the night before. He speaks eagerly of groups like The Strokes and The White Stripes, and is modest but gracious when told that he and his band Blondie have informed and influenced the music of many bands, new and old. He is excited by the release of the ne CD, The Curse Of Blondie and the subsequent touring it will mean…

Rhythm: What made you choose the drums?

Rhythm: What made you choose the drums?

Clem Burke: “Well, my dad was a society drummer and there were drums around the house. I think the first record that hit me was probably ‘Wipeout’ by The Surfaris, which is kind of appropriate, and then The Beatles records, of course. I’m left handed, even though I play right handed, and I had trouble picking up the guitar when I was a kid, so I moved over to drums…”

R: And you set them up like you saw everyone else set up?

CB: “No, I took lessons and they were set up that way.”

R: Was that ever a problem for you?

CB: “No, I think it helps. I think Ringo is left handed.”

R: He leads with his left…

CB: “That’s what I do, but lately I’ve been practising leading with my right hand. When I do 16th notes on the hi-hat, I come down on the snare with my left hand instead of my right hand. It’s actually closer to the snare, but I think it’s helped me with something like ‘Rapture’, but now I purposely try to lead with the right. I think some of the quirks in my drum playing might have given me some of my ‘style’, oddly enough.

“I have a drumset in my house and I try to play every day, playing along with records and recording grooves. I don’t really sit down with a book of rudiements or anything.”

R: So you took lessons as a kid?

CB: “Yeah I did for a while, and then I was in drum and bugle corps. It really helped me with endurance and with chops, I think. I played rudimental bass drum too. It’s pretty ridiculous. I took Orchestra in grammar school too…”

R: What was the first band you were in?

R: What was the first band you were in?

CB: “I had bands all through high school – that was my social scene. It was a good way to meet girls. It was that whole thing of why people get in bands – it was the camaraderie of a whole group of people. I had a band my first two years of high school and another band my second two years. We would win Battle Of The Bands, and there was this DJ in New York, Bruce Morrow, who had this show called Cousin Brucie’s Big Break where everyone sent in music. I think we recorded on a mono reel-to-reel tape recorder, and you sent that in and if you get selected he plays it on the radio and then you get to go into the recording studio. We were selected and we won and we went to ABC studios and recorded. That was my first recording session.”

R: What was the name of that band?

CB: “Total Environment (laughs). We had a light show, the whole thing. The thing was we got selected to be on Cousin Brucie’s Big Break and you’d get to play live at some big place and that year it was at Carnegie Hall – so I was 14 years old and I got to play at Carnegie Hall.

“So I was always in bands at the time. I was in an art rock band and we played a high school assembly and we did ‘Peaches en Regalia’, the Frank Zappa tune, with full-on band and vibes, timpani, keyboards. I think we went into ‘Willie The Pimp’ by Captain Beefheart after that.”

R: What was your first drum kit?

CB: “I wish I still had it: it was a Radio King kit. It was the one with the tacked bottom head. We traded it in for a Rogers kit like Dave Clark of The Dave Clark Five had. It was White Marine Pearl.”

R: How did you end up in the New York scene?

CB: “Well, things kind of shifted with me. I was a big New York Dolls fan and a big fan of David Bowie, Roxy Music, Cockney Rebel, The Sweet, T-Rex. Basically, the friends I knew who were into Zappa and Beefheart didn’t like that stuff at all. So I found people along the way who were into it, and one of those people was Gary Valentine, the original bass player in Blondie, the guy who wrote ‘X-Offender’, the song that got us our deal.

“We used to go to a place called the Club 82 on East 4th Street and 2nd Avenue. It was a transvestite/lesbian bar that one night a week would have rock bands such as the Dolls, or Wayne County And The Electric Chairs, The Neon Boys, which was the band Tom Verlaine had before Television. Lenny Kaye and Tommy Ramone and people like that would hang out there. Joey Ramone was in a glam band called Sniper. I had a band called Sweet Revenge and we played at the Club 82 a couple of times – that was our goal, to play there.

“Along the way, Debbie Harry and Chris Stein had a band called The Stilettos which would open for the New York Dolls at Club 82. That glam rock scene kind of died down and coincidentally, right around the corner from there was CBGB’s, so everyone cut their hair and started wearing leather jackets and moved around the corner and started hanging out at CBGB’s. My quote is that there were no ‘punks’ at CBGB’s – it was more like bohemian, outcast type of people. It was like a clubhouse for beatniks with about 100 people. I was like 18 years old, just a kid on the streets of New York and by that time we got a storefront on the Lower East Side where we would crash in. I knew Debbie and Chris were looking for a drummer so I went along to an audition, and we sat around for the whole time and we had a lot of common interests in music and the arts, people like Burroughs and the MC5 and The Velvet Underground, but also The Ronettes and bubblegum rock. We went on to play a couple of songs. Fred Smith who would later be in Television was playing bass with them then, and Ivan Kral, who would go on into Patti Smith’s band was in with them.

“The first gig was two nights we had booked at CBGB’s and the first night Fred Smith announced he was leaving to join Television. I brought my friend Gary Valentine into the band and then we had the nucleus of what came to be Blondie. That was in early 1975.”

Was there an awareness at that point you were all part of something special?

“No. The awareness was that Debbie had a special charisma that I was taken by. My whole thing was that I wanted to find my Marc Bolan, or my David Bowie or Mick Jagger. I wanted to find somebody with that much potential. They had some interesting songs and they were doing original music, and I wanted to play original music. I wasn’t very much interested in being a club band. My whole goal was to be on a record that was in the cut-out bin at Woolworth’s. That’s where I used to buy my records and that’s where I thought hip, good records ended up, in the cut-out bin.”

It’s pretty amazing how that scene had such an impact on music and was so influential for the next 25 years.

“Yeah, I guess you could say it was like our version of the Cavern Club. The think about CB’s was that we were allowed to develop in public. We weren’t particularly good when we first started, but we were writing and performing and we were able to do it in front of people, which I think might be a better way to learn how to do it. I’m not really big on people staying in their houses and practising all the time and never feeling as though they’re really good enough to play out. I think it’s really counter-productive if you want to be a professional musician. There’s a lot more to it than how proficient you are as a musician – it has a lot to do with presentation, not being nervous in front of audiences and all that. I think people get more worried about being junior Dave Weckls, instead of really getting out there and just doing it.

“I learned a lot from our producer, Mike Chapman, who was a big songwriter in England in the ’70s. He wrote ‘Ballroom Blitz’ and a bunch of songs and was really very successful, and he really helped us with our song writing and he made Parallel Lines the record that it became. Honestly, without him, we wouldn’t have been able to do it.”

You seem like you were more of an accomplished drummer than many of the other drummers who came out of the New York scene at the time.

“I have a couple of theories about that. A lot of it had to do with the fact that no one could really play, including myself. I got this reputation early on for being a good drummer and that’s because a lot of people who were around sucked and couldn’t play at all. I had some experience by then and had played in high school and so on, and a lot of people had never played an instrument.

“In Blondie, although Chris is a really innovative guitarist, he wasn’t really that solid, so I think I developed into a better player because I had a lot of holes to fill. I also think that working with producers like Richard Gottehrer, who produced our first two records and wrote great songs like ‘My Boyfriend’s Back’ and ‘I Want Candy’, and Mike Chapman, who produced four of our big records, was important for helping us focus on making good songs and it definitely helped my drumming. I learned how to play for the song and be more minimal in my own playing, but also how to give it that extra boost. I was influenced by Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer, and the music they did with Phil Spector. I was talking to Don Randee, who works with Nancy Sinatra and was on all those great Spector songs, and he said that Phil wouldn’t let Hal play any fills while they were rehearsing the songs. Then, when they did the take, they really had all this pent-up energy and it gave those songs that excitement.”

With all of the big hits Blondie has had, was there ever a song that you heard early on in the process, where you just knew it was going to be a hit?

“‘Heart Of Glass’ was buried in Parallel Lines – we never thought of it as a single. We thought it was too weird with the sequencing and the drum machine at the beginning, and that became our first Number One single in the US. We never really knew what was going to be a hit. A big controversy in Blondie is how ‘Heart Of Glass’ evolved into what it became. Mike Chapman takes credit for it, but the song was kicking around for a long time. It was on our first demo, but not in that vein. The way I remember it was that Saturday Night Fever was a record I really, really liked, and one day we were kicking around ‘Heart Of Glass’ and I figured I’d just do this JR Robinson thing. I didn’t know it was him at the time, but I just wanted to do this Bee Gees ‘Night Fever’ type of groove. That’s how I remember it. (laughs)

“Mike Chapman was a real taskmaster, but when we did Eat To The Beat, the reason why ‘Dreaming’ came out the way it did is because he really gave me free rein and it was really a surprise. That take of ‘Dreaming’ was just me kind of blowing through the song. It’s not like I expected that to be the take. I was consciously overplaying just for the sake of it because it was a run-through. I always say ‘Dreaming’ would have been a bigger hit had I not played like that. It was Top 40, but it was never a huge hit. ‘Atomic’ was another one off Eat To The Beat that was just kind of a joke and it ended up going to Number One in the UK. We just kind of blew it out real quick.”

Has the recording process changed for you guys?

“It’s changed but it hasn’t changed. When we did ‘Call Me’ with Giorgio Moroder, it was the first time I ever played to a sequenced, pre-existing track, which was still a new thing back then. We did the song in one afternoon and didn’t think about it until we heard it on the radio months later and it sounded faintly familiar and we realised it was us. That’s another one that went to Number One and really came at a good time for us.

“Now, with the new record, there were lots of sequenced parts, and there are other songs that have live drums. So, yes, things have changed quite a lot, because on this record people brought in work they had done in their home studios, but there’s still some of the same aspects to recording.”

How would you describe your drumming to someone who’s never heard it?

“I would like to think of it as a kind of assimilation of Ringo meets Al Jackson meets Keith Moon with a little Earl Palmer thrown in. But that’s just naming names. That’s the great thing – learning from other people.”

One striking aspect to your playing is how you’ve always held your composure while you were playing some very uptempo grooves and impossible fills. Your style is very physical, and yet it seems like you never speed up or lose the feel.

“It’s funny when you think that all the classic Blondie records were never done to click tracks. With Eurythmics, though, everyone thinks it was programmed with click tracks, but actually everything was played live, with no computer, no sequencing.”

You mentioned Keith Moon – there’s a lot of Keith’s style in your playing. It always seemed to me you’d fit well with The Who. Were you ever approached by them?

“No. I worked with Pete Townshend on White City but, no, I was never approached by them. I think Zak Starkey is fantastic with them and they couldn’t have gotten a better drummer. I’ve known Zac for a long time and we try to keep in touch. I’ve seen him play some amazing shows with The Who.

“The day Keith Moon died, I was in Rotterdam, on my way to play three sold-out shows at the Hammersmith Odeon. I went downstairs in the hotel and all the British tabloids had the headline ‘Keith Moon Is Dead’, so that day became kind of a dream sequence for me. We played the Hammersmith Odeon and I wanted to get some gasoline and an axe to use on the drums and no one would give them to me. So I threw my whole drum kit in the audience, not wanting them back, because I wanted to sacrifice them for Keith. And the roadies went and got them back, which I was upset about. It was a real emotional time for me because he had meant so much to me. But I’m really proud of having worked with Pete and he’s a really great guy. All that crazy stuff is definitely not true.”

‘Rapture’ from 1980 was such an important song in the history of hip-hop, and yet Blondie was a band playing what was basically new wave pop music.

“We worked with the Wu Tang Clan on a remix of a song called ‘No Exit’ and they’re totally hard serious gangsta rappers, and they said the first rap song they ever heard was ‘Rapture’. It would have been funny to be walking around New York in the ’80s near the public housing and see these little kids outside singing the rap from the song.”

How long do you think Blondie will go on for?

“We’ve decided to continue on with the band because we’re partners in it and we enjoy playing together. We’ve finally realised what we should have years ago: Blondie is a tremendous home base for us. We can all do our other projects or not, but there’s that home base for us to come back to. It’s a way of having a career and respect in the music business, and a way of earning a living. I’m happy to be able to make records. I’m happy to be a performer and to tour at this stage in my life. I feel we’ve proven everything there is to prove.

Clem Burke

ESSENTIALS

CLEM’S ESSENTIAL TRACKS:

Blondie

‘Rapture’

From Autoamerican (1980)

Blondie

‘X-Offender’

From Blondie (1976)

Blondie

‘Attack Of The Giant Ants’

From Blondie (1976)

Blondie

‘Hanging On The Telephone’

From Parallel Lines (1978)

The Plimsouls

‘Playing With Jack’

From Kool Trash (1998)

“My homage to Keith Moon”

ESSENTIAL DRUM SOLO AND DRUM TRACKS:

Rod Stewart

‘(I Know) I’m Losing You’

From Every Picture Tells a Story (1971)

Drummer: Mick Waller

“It’s so melodic and spontaneous”

The Beatles

‘Birthday’

From The Beatles aka The White Album (1968)

Drummer: Ringo Starr

Jeff Beck

‘Beck’s Bolero’

From: Truth (1968)

Drummer Keith Moon

The Rascals

‘Cute’

From Freedom Suite (1969)

Drummer: Dino Danelli

The Who

‘The Ox’

From The Who Sings My Generation (1965)

Drummer: Keith Moon

The Ronettes

‘Be My Baby’ (1964)

Drummer: Hal Blaine

“Anything by Earl Palmer, especially with Little Richard. Anything by Kenney Jones with The Small Faces.”

FAVOURITE DRUMMERS

Hal Blaine

Earl Palmer

Ringo Starr

Keith Moon

Jerry Nolan

Al Jackson Jr.

DID YOU KNOW THAT…?

Dr. Marcus Smith of University College in Chichester has been studying Clem for a scientific research project aimed at “increasing our understanding of the physiological demands associated with playing the drums during a live concert”.

“He attaches a meter to read my heart rate and pulse while I’m performing,” explains Clem. “He does a check before I do the show and then monitors me from song to song to study what effect the performance has on my body.”

Clem’s Drums:

Premier Genista Silver Sparkle

24″ bass drum

16″ floor tom

18″ floor tom

14″ rack tom

14″x5½ snare

Cymbals:

Zildjian

14″ K hi-hats

18″ A Custom crash

10″ A splash

19″ A Custom crash (2)

22″ K Heavy ride

19″ K Custom Dark china

16″ A Custom crash

30″ orchestral gong

Plus…

Remo drum heads,

Vic Firth 5A drum sticks

PLAY ALONG TO…

BLONDIE, ‘CALL ME’

Slam in your Rhythm CD and prepare to play the Clem Burke way! Poptastic!

Your Tutor: Pete Riley

Great pop music doesn’t come any classier than Blondie, and with this month’s Guest Editor Clem Burke in the driving seat, there’s plenty for us drummers to get our teeth into as well. The Giorgio Moroder-produced classic ‘Call Me’ was a UK Number One in 1980 and featured prominently on the soundtrack to American Gigolo, which made a star of Richard Gere.

The track features some sequenced parts which was a relatively new concept then. These include an eighth-note-triplet based keyboard line and hi-hat part, which run throughout the track. Being able to lock in with a part and play all of the subdivisions in this way is a serious challenge and it’s a testament to Clem’s drumming which is unmoving from beginning to end (we won’t mention the possible edit at 0:51!).

The top of the tune kicks off with a one bar eighth-note-triplet fill and launches into a driving triplet based four-on-the-floor groove containing the signature Clem Burke hi-hat moves. At this time, the disco era was coming to an  end and the drum machine was making its presence felt in electronic pop and early hip-hop. Clem’s playing perfectly fused the attitude of a real drummer with drum machine accuracy and repetition of part – especially on the hi-hat. Whilst on the subject of hi-hats, the sequenced hi-hat track running throughout makes it difficult to discern exactly what Clem is actually playing. On first listen it’s easy to assume he’s playing hand-to-hand eight note-triplets when in fact he leaves the subdivision work to the sequencer and instead sticks to swung eighth notes.

end and the drum machine was making its presence felt in electronic pop and early hip-hop. Clem’s playing perfectly fused the attitude of a real drummer with drum machine accuracy and repetition of part – especially on the hi-hat. Whilst on the subject of hi-hats, the sequenced hi-hat track running throughout makes it difficult to discern exactly what Clem is actually playing. On first listen it’s easy to assume he’s playing hand-to-hand eight note-triplets when in fact he leaves the subdivision work to the sequencer and instead sticks to swung eighth notes.

Ex 1 shows the initial fill and the following four bars where Clem sets up the four-on-the-floor feel. Ex 2 shows the two bar fill leading into the second chorus, which moves single strokes off the snare drum and around the kit. The next example shows the fill that leads out of the second chorus and the following four bars leading into the middle eight. Watch out for the 2/4 bar at the end of the middle eight (Ex 4) and keyboard solo. This track contains all the trademark Clem Burke-isms, from the hi-hat ideas to round-the-kit and all-round rock attitude. I think you’ll have a lot of fun playing it – see you next time.