Hit Parader

December 1981

December 1981

BLONDIE

PROUD DARK ROOTS

Debbie Harry Goes Beyond The Valley Of The Dolls by Roy Trakin

When we last left Blondie’s Chris Stein and Deborah Harry back in December, Autoamerican had just been released. Owlishly-wise Chris was predicting it would get played on all the black radio stations. Sure enough, with two chart-topping singles, one reggae-based (The Tide Is High), the other, rap, born on the South Bronx streets, (Rapture) Autoamerican proved Blondie’s crossover potential on the street, where it counts.

Flushed with their successful forays into disco and rhythm and blues, Harry and Stein sought a fresh approach for Debbie’s debut solo LP. For production, they picked Chic’s Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards. The result, KooKoo, hits the album-oriented rock world like a blast of fresh air.

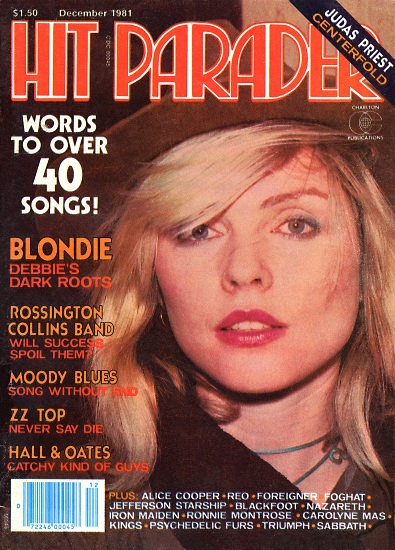

The cover is a startling photo of Debbie with hair pulled back and grown out to her natural shade of mousey brown. It was designed by the great Swiss artist Hans R. (Alien, Brain Salad Surgery) Giger, whose final touch was four large acupuncture needles piercing Debbie’s face. The full-size blow-up of the album jacket is the first thing that greets me as I enter their apartment. I wondered if its starkness was an attempt by Debbie to de-glamorize her image as Blondie.

“We did want to cut down a little on the exploitation end of it,” explains Chris Stein, adjusting his horn rims. “Maybe it means Debbie’s just sick of her face. It’s hard to say, but I’ve never liked the merchandising of Blondie and all that crap. We’re just trying to cut it down a bit.”

Chris insists Blondie is still a group, even though they have no set plans to tour together. Most of the rumors you hear these days center around Chris and Debbie going on the road with Nile, Bernard, drummer Tony Thompson and the rest of the Chic crew. After hearing KooKoo, such talk begins to make a lot of sense.

Instead of the expected funk/disco excursions that the Chic/Blondie collaboration was supposed to produce, KooKoo proves that both parties ended up influencing the others fairly equally. Rodgers and Edwards contribute pop gems like Backfired (the first single), Surrender and the stunning ballad Now I Know You Know, perfectly tailored for Deborah’s sultry, little-girl-grown-up vocals. On the other hand, the Stein/Harry forays into rap (Military Rap), reggae (Innercity Spillover) and funk/disco (Jump Jump, with Devo’s Gerry Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh) are right on the mark, thanks to the instrumental prowness of Nile Rodgers’ guitar riffs, Bernard Edwards’ steady bass and Tony Thompson’s precise drumming.

“It was a total collaboration,” agrees Stein. “The stuff that I wrote was very consciously for Debbie and them. They were doing the same thing – writing for themselves and Debbie.”

The Caribbean flavor of Innercity Spillover illustrates the street sense that tunes in Chris and Debbie to their audience. The lyrics mention “red card,” slang for those three-card monte games foisted by New York street hustlers on unsuspecting marks.

The Caribbean flavor of Innercity Spillover illustrates the street sense that tunes in Chris and Debbie to their audience. The lyrics mention “red card,” slang for those three-card monte games foisted by New York street hustlers on unsuspecting marks.

“We’re speaking the genuine language of the street rather than commenting on it,” insists Chris.

“The story which begins that song, about the brick falling on the girl’s head, is true. It was in the New York Post and Debbie picked up on it. I think Innercity Spillover is both a statement and an incitement.

It’s good coming from us. We never made statements like this with Blondie. We were more focused on entertainment.”

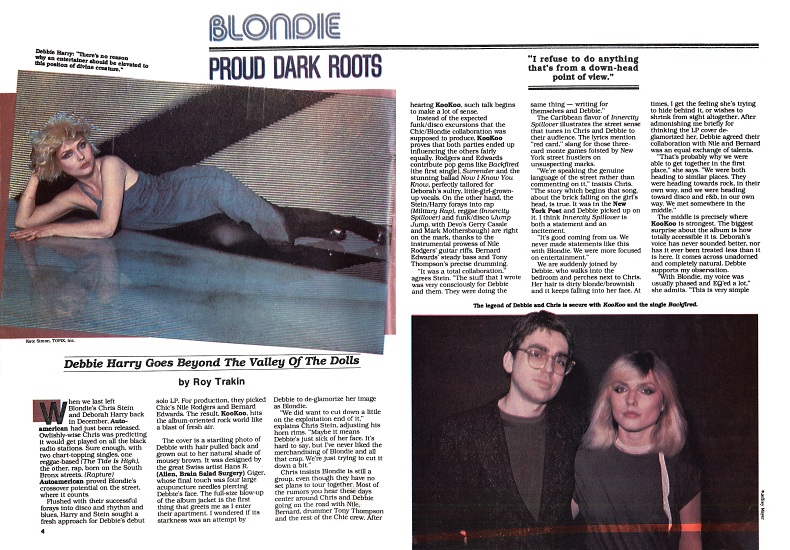

We are suddenly joined by Debbie, who walks into the bedroom and perches next to Chris. Her hair is dirty blonde/brownish and it keeps falling into her face. At times, I get the feeling she’s trying to hide behind it, or wishes to shrink from sight altogether. After admonishing me briefly for thinking the LP cover de-glamorized her, Debbie agreed their collaboration with Nile and Bernard was an equal exchange of talents.

“That’s probably why we were able to get together in the first place,” she says. “We were both heading to similar places. They were heading towards rock, in their own way, and we were heading toward disco and r&b, in our own way. We met somewhere in the middle.”

The middle is precisely where KooKoo is strongest. The biggest surprise about the album is how totally accessible it is. Deborah’s voice has never sounded better, nor has it ever been treated less than it is here. It comes across unadorned and completely natural. Debbie supports my observation.

“With Blondie, my voice was usually phased and EQ’ed a lot,” she admits. “This is very simple and straightforward. This is what I really sound like, what people hear in concert. With Blondie, everything was compressed more.”

That vocal openness is paralleled by an emotional directness that comes across on such personal songs as the gently psychedelic angloid-pop of Chrome, where Debbie talks of shedding images like a chameleon.

“Yeah, I’m not in character on this LP,” suggests Debbie as Chris interrupts with, “We never analyze our songs until later, though.”

“It’s just a fantasy based on Truman Capote’s book” (Music For Chameleons), says Debbie.

Does Debbie feel shackled to the image of Blondie as it’s written about in the media?

“I don’t think what’s in the press has anything to do with Blondie,” says Debbie. “What I dislike is that people  analyze me the way they see me, not objectively, and say, well, this is what’s there. Blondie is certainly a part of me; it’s a part of everybody that’s in it and it’s like a cartoon, kitsch kind of pop thing. I’m not trying to shed it.

analyze me the way they see me, not objectively, and say, well, this is what’s there. Blondie is certainly a part of me; it’s a part of everybody that’s in it and it’s like a cartoon, kitsch kind of pop thing. I’m not trying to shed it.

“True criticism should be a reportage on what the event is, a definition and then a critique from a personal point-of-view. Today, all you get is opinion and not the true picture of what it is the critics are talking about.”

Did Debbie think letting her hair grow out to its natural color would be a page three story?

“It’s just trendy,” she shrugs. “It’s gossip. Now, if you care to ask me what we can infer about the state of a world that puts such trivial gossip on page three, well…

“There’s no reason why an entertainer should be elevated to this position of devine creature, when they are just performers. There should be a limit to how much of a person you can expose.”

On the Rodgers/Edwards ballad, Now I Know You Know, fully in the tradition of such Chic classics as At Last I Am Free, Debbie Harry’s voice soars above the lush arrangement, giving lie to all those who’ve criticized her singing ability. How much have Debbie’s vocals improved over the years?

“It’s all a matter of concentration, like anything else you get better at,” says Ms. Harry. “You get more direct, you overcome inhibitions. You override your ego and become more selfless. It’s all in the breathing. You have to use your head and your chest. When I’m recording, I think about putting overt expression in the sound because the listener is not there to see the emotion.”

What was the relationship in the studio between her and Nile and Bernard as producers?

“That’s a personal question, isn’t it Roy?,” Debbie mock-scolds me. “I will tell you one thing: what they say about black men is true!”

The success Blondie achieved from covering two black idioms (that had never before earned a large amount of sales), had many purists grumbling that whites were once more exploiting the original forms by commercializing them.

“Both The Tide Is High and Rapture happened to be Chris’ brainstorms,” says Debbie. “But, that’s always been our thing – to be timely and new with something that’s sort of semi-controversial and has never really been successful.”

“If Grandmaster Flash and the rest of the rappers got played on the radio as much as Rapture did, they’d have hits, too,” says Chris.

“In a sense, we played the market by approaching it to get airplay from day one,” confesses Debbie. “Once we were on a label, that’s how we went about it, and we worked real hard toward that end. It took a while for us to get in the position where disc jockeys would play our records, but once they start, they keep working for you. But, we never have gotten F.M. play. We’re strictly a Top 40 band. We always said we were a pop band. Everybody else called us everything from shit to shinola…”

Previously, Bernard and Nile admitted to me that they considered producing Debbie’s solo debut their own gateway to pop acceptance.

“Yeah, and in the same way, these guys who are some of the best pure players in the business on any level, so far undiscovered in the white rock market, are going to have a record that’ll freak out those people. I’ve known about them since I first heard Le Freak,” says Stein.

“People aren’t even aware that Bernard and Nile play instruments,” adds Deb. “They think Chic is made up of studio musicians. These guys are the black Cream, believe me.”

Will that white rock audience ever accept black music or black musicians playing rock and roll?

“Personally, I don’t think it has anything to do with music,” says Debbie.

“When black people are more accepted, their music will be more accepted,” says Chris. “In fact, the music is still more accepted than the people.”

“Yeah, it’s just racial,” Deborah agrees.

“I found that, after hanging around with Nile and Bernard a while, I began to feel black people were superior,” laughs Stein.

“Especially when the two of them went into their riffs about white people. All they do is tell race jokes and carry on whenever we tried to get them into a serious conversation. I grew up in Brooklyn with a lot of black kids around. To me, there’s no distinction at all. I don’t make any judgements.

“If anything, I think Bernard and Nile’ll be accused of being too white, bit I still believe the music speaks for itself.”

“People just need an excuse to be vindictive. If a bunch of spacemen or aliens landed down here – and they were green and slimy – believe me, blacks and whites are all of a sudden gonna look real good to one another. That’s where it’s at,” concludes Debbie with the common sense viewpoint that made Rapture’s rap about the Man from Mars who eats bars, cars and guitars so transcendent. After all the hoopla, it’s a message of faith and optimism.

“I refuse to do anything that’s from a down-head point of view,” says Debbie. “Nothing that’s depressing. I don’t like to write like that even though sometimes I might personally feel like that. I don’t want to foist that on other people. I won’t personally take people into the depths of hopelessness.

“After all, I’m an actress. It’s part of my job to entertain people, y’know. That’s what it’s all about, I guess. To let people have an area where they can express that themselves. Even if it is through another person. That’s why everyone interprets lyrics differently.”

“I think everybody has the potential to be Debbie or like Debbie, but they just aren’t aware of it,” says Stein. “Debbie has a universal identification.”

Absolutely true. In a sense, Deborah is just an ordinary girl, the cheerleader-next-door type that Middle America forgives for her eccentricities because, oh well, everyone who lives in New York’s gotta be a little crazy, right? But it still doesn’t explain everything. For that, we turn to Chic’s Bernard Edwards, who gives us another side of Debbie Harry.

“Debbie is so balanced, it’s unbelievable. I was shocked,” he says. “The image she projects is that of the original flaky blonde, but she’s a businesswoman, believe me. The first day she came in, we saw that right away.”

“We know it’s an expression/A silly little phrase/Not the doobell/Not a bird call/Koo Koo”

Poised at the threshold of her greatest triumph yet, blonde or brunette, Deborah Harry is no Kookoo, but one shrewd bird.