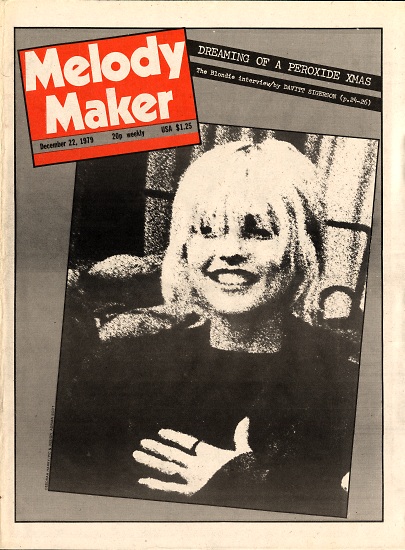

Melody Maker

Pages 4, 24, 25, 26

Page 4

BLONDIE SELL OUT AND ADD DATES

BLONDIE have sold out three concerts at London’s Hammersmith Odeon, and have now added a fourth night as part of the tour that starts just after Christmas.

The new concert, on January 20, follows the demand for tickets for the previous three nights of January 11-13, and 1,000 seats will be reserved for Blondie fan club members, with tickets at £4.75, restricted to two per member, available with a cheque or PO, sae and membership number from the box office.

Blondie have also added another night at Deeside Leisure Centre on January 19 to follow the original show on January 6.

The band leave Britain after the Hammersmith shows for some Paris concerts before returning for the two extra shows at the end of the tour.

Your

instrument

is your

body

ALL PIX: ADRIAN BOOT

Debbie Harry and Chris Stein don’t see their music as high-tech. Mostly it’s organic, responsive, more emotional. DAVITT SIGERSON faces up to The Face

PEOPLE remember the face as they see it in photographs, that’s axiomatic. And her face possesses that photographic stillness even in life – not as herself, in a room, but when she’s Blondie, wry international supergirl. As themselves, in a room, Chris Stein and Debbie Harry are your average kooky sidekicks, twisty trysters abroad in the post-democratic Western world. There’s a need to separate Debbie from the ikon she animates: because Blondie’s her own girl, and because it puts the band’s backs up when people think they’re Harry’s hired hands (they’re not, they’re Blondie’s). Blondie has everything it takes to be big – the cold perfect stillness, the role confusion (maybe it’s Debbie’s after all, since she puts most of the words in her character’s mouth).

Like Garbo in the last reel of “Camille”, like every R&R sexqueen from Summer to Rondstadt to Nicks to Kate Bush, Blondie supplicates. Of course she doesn’t have to, with a face like that, and yet she’s always the one who’s coming on. That’s a perfect fantasy, so men like it, and women like it too: because they can sing along, and because they aren’t being threatened by a competing Hot Bitch.

There’s a trick of course, that constant undertow of irony. In a way we absolutely believe the skewed vision (“I will give you my finest hour/The one I spent watching you shower”), and in a way we don’t. Is it what you call too clever by half? This doll, then, is similar to her prototypes, but more likeable (wittier) and probably, in sum, less fanciable (sincere, flattering). So maybe Blondie will remain a singles band, relying, for all its imagistic potency, upon the strong song.

I spoke to Chris and Debbie after rehearsals for their European tour. “Eat To The Beat” has yet to match the  market performance of “Parallel Lines” (hardly surprising, it isn’t nearly as good). Stein plays three tapes: first his music for Debbie’s first feature film, “Union City”. It’s quite good, in a “Taxi Driver” way (Stein makes the reference). He plays part of an album on Ze he’s produced. The act is Casino Music, a pair of high-fashion French disco boys with rhythm-boxes, sequencers, songs called things like “Faites Le Proton”, and a club-minded remix by Chris Blackwell. Finally, he plays snippets of a ripping 6/8 rock disco number, “Call Me”. Debbie wrote the tune with producer Giorgio Moroder, who will edit these fragments into a master.

market performance of “Parallel Lines” (hardly surprising, it isn’t nearly as good). Stein plays three tapes: first his music for Debbie’s first feature film, “Union City”. It’s quite good, in a “Taxi Driver” way (Stein makes the reference). He plays part of an album on Ze he’s produced. The act is Casino Music, a pair of high-fashion French disco boys with rhythm-boxes, sequencers, songs called things like “Faites Le Proton”, and a club-minded remix by Chris Blackwell. Finally, he plays snippets of a ripping 6/8 rock disco number, “Call Me”. Debbie wrote the tune with producer Giorgio Moroder, who will edit these fragments into a master.

MM: That really runs.

Stein: It’s a heavy song, a real kick-ass song. It was totally different from working with Chapman, it was very loose. Giorgio recorded the sequencer in LA, as a click track, and we played over that.

MM: The sound and structure that Chapman started getting on Blondie records seems to be cropping up on other Chapman and Peter Coleman records, especially on dance music.

Harry: We’ve noticed the same thing. But then you could say that about Chapman’s work with Sweet and Suzi Quatro.

MM: Sure, but Chapman wrote those. For instance “We Live For Love”, Pat Benatar. That’s great, but…

Harry: Chapman told us he was gonna do that.

Stein: It’s good for us because the more people that copy us, it just expands our market.

MM: How much of that came from you? When you used to do “Heart Of Glass” on stage, was that as a disco song?

MM: How much of that came from you? When you used to do “Heart Of Glass” on stage, was that as a disco song?

Stein: More like funk, like an Ike & Tina type, like “Sexy Ida”, or “Nutbush”. We used to do “Sexy Ida”.

MM: So whose idea was that treatment?

Stein: It was really everybody’s, Jimmy’s, but it was inspired by Giorgio and “I Feel Love”, and Kraftwerk.

MM: There’s nothing like it on “Eat To The Beat”, including “Atomic”. Did you feel any pressures to “follow up”?

Harry: There was a certain amount of pressure on us to do something that would do what “Heart Of Glass” did in the business world.

MM: When that was number one, David Byrne remarked to me that he thought bands like Blondie and Talking Heads would never have consistent pop hits in the U.S. He felt the American public was too regimented.

Harry: It doesn’t have anything to do with the public. It’s the market and it’s the business and the radio programmers. And they’ve all come around – because the record business has had to change their approach because they can’t bank on one multi-million dollar group. They have to band on a lot smaller groups.

MM: But you think it’ll happen.

Harry: Oh yeah, it’s just slow.

MM: You don’t think maybe people here are stupider than, say, in England?

Harry: Not the kids.

MM: Would it be fair to describe Blondie music as pastiche?

Stein: In the sense of…

MM: In the sense of it being very consciously referential.

Stein: Definitely. But all music is referential, and that builds up, because as time passes, there are more and more things to make reference to. The Stones were referential too, but to one thing.

MM: Yes, but there’s a more cerebral quality. “Slow Motion”, for instance, is so Motown.

Stein: Yeah, well that’s really – the tambourine. But some things are less specific. Like “Dreaming”, which is a mish-mash of a lot of things. It really was supposed to be more disco-rock than it came out. The bass drum got swamped by the tom-toms. “Atomic” I think is a great example. It’s disco, Ventures…

MM: With a little Christmas carol.

Harry: Yes. On this tour we decided that we would do rock versions of Christmas carols for our English holiday tour, and then we’re gonna do a live album of Christmas carols from the Hammersmith Odeon.

MM: On “Atomic” your disco percussion break is rhythm-box. That’s cerebral.

Stein: That wasn’t conscious.

Harry: It goes along with the cover design.

MM: In what way?

Harry: You know, high-tech.

MM: That’s true, but not of the rest of the album. It’s more emotional.

Stein: It’s a lot more organic.

MM: Sure! If “Dreaming” started out as disco…

Harry: We had a technical problem with compression and eq, and we lost a lot of the drum tracks.

Stein: That got changed around. If you ever heard my demo with the rhythm machine… but some of them… “Shayla” came out just the way I want.

MM: (to Debbie): Your singing has become a lot stronger, even as of the last album. Your pitching and tone are working much better now. What have you done?

Harry: I think my recording technique has really improved. For a singer it’s different from an instrumentalist, trying to be so precise – but you’re human, your instrument is your body. It’s a lot different when you’re banging on strings or skins.

Stein: The transition from performing live is also difficult.

Harry: I know it was difficult for me. The first two albums, with Richard (Gottehrer), I would do three and four major vocals in a day, and all the harmony parts and back-ups. I would never do more than three takes on a lead vocal. I would try to go through the whole song, not just verse by verse. With Mike it’s much more careful, and I’m much more discerning about it myself. Now I usually do two leads in a day, and sometimes a few harmony parts. When you sing, you go for the timing, the phrasing. You go for the note, for correctness. And then you have to go for the attitude. So there’s three things you have to get all at once. The note-for-note things I take for granted, because either you hit it or you don’t, and if you don’t you just do it over. But the most important thing is the attitude. Sometimes if you put a lot of feeling into a note, it’s bent – and it doesn’t matter, because it makes it.

MM: Your voice is very rich. It hasn’t got the thinness, the edge of many pop voices. That’s a nice contrast.

Harry: I know what you mean. I like that too.

MM: You’ve been adopted lately by a pretty ritzy crowd. Do you ever feel used, or maybe compromised?

Harry: We try to take what we want. You’ve got to make your selections from whatever the influences are. We’ve never been the kind of people to belong to any cliques. Most people we’ve been affected by have been both very nice to us and very horrible. We’ve been horribled.

MM: I just wonder about a kind of moral relativism. Like at college, I never knew what I felt about friends whose fathers happened to be officers in the Savac. They can be very nice, and yet they’re beneficiaries of so much evil. I think Andy Warhol has a lot to do with that… suspension of moral judgement.

Stein: I like Andy, I have a lot of admiration for him, as an artist. And whatever anybody says, he’s been the fucking kingpin of the New York art scene for years. Also, I think he’s been very radical.

Harry: But he couldn’t put any kind of direction on the horribleness that was around him, and I think in that period after he was shot, he really changed. I think that one of the best things that happened in the Seventies was the thing that the Sex Pistols did and Malcolm did. Even though it ended in total destruction, it was successful in a lot of ways. I suppose I haven’t reached my final definition of what that was, but it was something really great from an artist’s point of view – not a record company’s maybe.

Stein: I don’t know how anybody can care about creating a lasting art form, because I believe we’ll be destroyed, I mean the West. It seems so…

Harry: Yeah, but how can you be upset about that? I mean, what does it matter? It’s all in your head.

Stein: Because if I was… I’d fucking go live in the mountains and make art in a time capsule and bury it. Or just play guitar and never record anything.

MM: So “Die Young Stay Pretty” is meant ironically.

Harry: Definitely. I wouldn’t…

“The acquisition of my tape recorder really finished whatever emotional life I might have had, but I was glad to see it go. Nothing was ever a problem again, because a problem just meant a good tape, and when a problem transforms itself into a good tape it’s not a problem any more. An interesting problem was an interesting tape. Everybody knew that and performed for the tape. You couldn’t tell which problems were real and which problems were exaggerated for the tape. Better yet, the people telling you the problems couldn’t decide any more if they were really having the problems or if they were just performing.”

– Andy Warhol, from “The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again)”.

MM: Four songs on the new album – “Dreaming”, “Union City Blue”, “Shayla” and “Atomic” – feel organic in a way the others don’t. With most of them, the idea seems to have preceded the music.

Stein: If Debbie and me worked by ourselves, it would all be like that. It’s true, I don’t know why that is. The others are very self-conscious.

MM: A song like “Dreaming” or “Sunday Girl” must be very easy to sing again and again. Aren’t songs like “The Hardest Part” or “Die Young” rather less exciting to do?

Harry: Yeah, but those are real audience songs. They’re not singerly but you deliver a line, and – it’s attitude.

Stein: There’s less of a melodic sensibility, it’s more archetypes.

MM: There’s something distancing about that, and about Blondie’s music in general. There seem to be more conceits than emotions.

Stein: There aren’t a lot of songs where Debbie just stands up and sings what she feels. They’re all pretty ironic. That’s just the way it is. But it has to do with this culture, the kind of cartoon things…

MM: There are exceptions, I’d say “Denis”…

Stein: That’s what I was gonna say too. But the subject matter – what do you sing about to masses of people? I feel OK to be writing about music. To sing about politics, like “Victor”, and be sincere about it… It’s difficult doing Jefferson Airplane, “Volunteers”, but it’s also difficult for me doing a straightforward love song, like the Bee Gees.

MM: For instance, “finest hour” is a great line…

Harry: Yeah, but it is a little hard to take.

MM: The very cleverness of it…

Harry: But see, one of the things that’s happening is, I’m saying things from a woman’s point of view, and it’s definitely different.

Stein: Maybe that’s it.

Harry: I really have to…

Stein: Yeah, but the Supremes came from a woman’s point of view. He’s saying…

Harry: Yeah, but they were a different point of view.

Stein: But what he’s saying is, there aren’t hardly any songs that I can think of that are just plain, straightforward sincere delivery.

Harry: yes. Maybe so.

MM: Think of the kind of songs people write…

Stein: It ain’t Carly Simon.

MM: Well, it’s not only Carly Simon that would want to sing or write a song from direct feeling.

Stein: We do come out of the new wave, which is a whole backlash about all that romance and that dumb emotionalism.

MM: But do you think all emotionalism is dumb?

Harry: No! But see, these things are so over-emphasised. We do the reverse, we under-emphasise. These songs are capsules. There are all these feelings, and what’s ironic is that it’s all happening at once and it all has happened to you. It’s something I can’t be totally objective about, but when you started saying that before, I really picked up on it.

MM: I wonder how the Debbie/Blondie split ties in to this whole business.

Harry: It’s beyond. I suppose sometime I’ll be able to think about that and really come up with some answer, but not… I think that maybe… You’re the first person we’ve talked to about this, but I think that, in terms of original rock’n’roll songs, and fundamental songs that are so direct, and pure, in that sense. I would like that to happen to me, and eventually I think that it will. But not to say that this is… Sometimes I think to myself, “Wow, how can you be so…” – I would like to be less intellectual about this. But yet, there’s a great degree of spontaneity. I don’t know what I’m trying to say really, except I know about that simplicity, the simple direct emotion, and as yet it really hasn’t happened.

MM: Hmm.

Stein: Debbie…

Harry: But even though everything seems so indirect, I can’t help thinking it really is direct. Maybe the way I’m expressing things is just new. My life has never been simple, it’s always been complex. It’s always been operating on many levels. And I don’t think there are very many people in the world that live simple lives.

Stein: It also comes down to politics a little. Because here’s Debbie, she is not coming from the streets, particularly, just a regular kid – what can she sing about besides, “I wanna screw you”? That’s about it. Maybe if she were black, that’s another subject she could sing about.

Harry: We’re sort of tottering on the edge of this pop thing, that’s totally legitimate and commercial, and something that’s totally suspicious. That’s the line we walk and that’s the image we have. The odd thing that happens is we have this number one hit all over the world. The really radical kids reject us because we’re too smooth and then the people that are “too smooth” look at us in horror and think that we represent radicals.

Stein: Maybe we can write a music business song.

MM: Please don’t.

Stein: But, like, that’s the alternative.

MM: Got your riff on the Eighties, yet?

Stein: More avenues will be explored – jazz, ethnic musics. I hope there’ll be more of a synthesis between white and black. I’m really down on people who are anti-disco, because that’s like being anti-impressionist painting. Not that I equate the two. But how can you be anti- any kind of music? I also foresee the fall of Western civilisation.