May 1976

Vol. 1 – #3

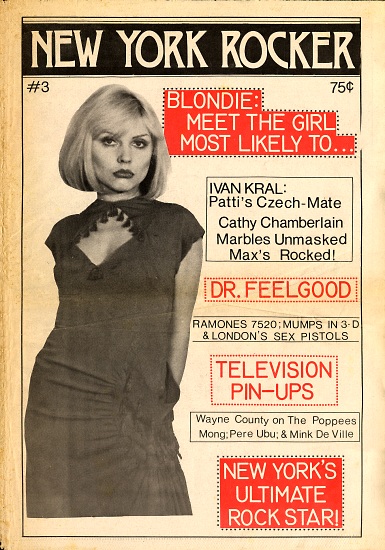

Cover photo by Lisa Persky

Pages 10, 11, 12

BLONDIE’S ROOTS

“Blondie was a street name I got from truck drivers. They always yell, ‘Hey, Blondie.’ Now all the bums on the Bowery yell out, ‘Blondie, hey Blondie.'” But long before all the primal screaming, ages before STET, she was quietly given the name of Deborah Harry in the most northern of southern towns, Miami. An early move to New Jersey erased any conscious memory of exotic southern mimosa, but some faint scent lingers. “My earliest memory is about this place where I went that was like a southern mansion with huge pillars and there were all  these animals in pens. I thought they were elephants and giraffes. In reality, what they were, when I was older and I asked about this memory, I found they were ducks. I thought they were elephants. It was some kind of family resort hotel.” A dream reality that confuses Southern Gothic with Jersey commerce–Tara plunked right down in the middle of Jungle Habitat. But Debbie’s family’s fortunes were less cinema-graphic than Miss Scarlet’s roller coaster ride. “We started out poor and we ended up middle or upper-middle.

these animals in pens. I thought they were elephants and giraffes. In reality, what they were, when I was older and I asked about this memory, I found they were ducks. I thought they were elephants. It was some kind of family resort hotel.” A dream reality that confuses Southern Gothic with Jersey commerce–Tara plunked right down in the middle of Jungle Habitat. But Debbie’s family’s fortunes were less cinema-graphic than Miss Scarlet’s roller coaster ride. “We started out poor and we ended up middle or upper-middle.

Debbie debuted her voice in a Hawthorne church choir when she was eight. At the time, it seems she was less than angelic looking. “When I was a baby, I was real pretty, but in between I was a real mess. I was very ugly. I just grew weird. I always had weird haircuts. My mother always made me get these weird haircuts and I always had to wear clunky shoes and shit. I never thought I was pretty.” Lolita emerged. She canned the choir and ditched the robes when she was 12 and “officially” began dating.

She loves ya right now

But don’t close your eyes

She’ll be talkin’ and laughin’

With six other guys

Flirtatious and cute

She’ll take you the route

Tellin’ Little Girl lies.

“Did you go around with people older than yourself?”

“Yes, as old as I could find them. The older the better.”

“Did you believe in kissing on the first date?”

“I was warned against it, but I did it because I really wanted to.”

“Were you considered fast?”

“I was talked about.”

Fast talk, but slow memories. “All I remember about high school was how boring it was. I made average and good grades at Hawthorne High School. I was never in any trouble. I was just steady. I was just there. I was a baton twirler for awhile. I don’t think that anything that I did in school was representative of me. You have to fit into the regime and you get through it.” However, there were sparks of spunk. “I got into a sorority. I had to run around and act a certain way, supply certain things upon command, like gum if they wanted gum. I was offensive to them, so I got canned. But the reason I got kicked out was because of this friend of mine who was really great, really nutty, but they thought he was too horrible. Mostly, because he was gay. They said, ‘You can’t hang around with him.’ So I got the ax. The girl that brought up the charges later on married him.”

And in at least one way Debbie got a hold of Todd Rundgren’s karma before he did. “I bleached my hair all the time. It was white and very long. I used to wear it up and I used to put vegetable coloring in it, different colors. I was an art student and you could write it off as that.”

Debbie had the look of a rebel–a greaser dressed all in black, driving a 25 dollar Chevy and listening to The Shirelles, The Ronettes and Smokey Robinson–but not the act. “It wouldn’t get me anywhere to be a rebel, except I’d always be punished and locked in the house. But I always stated what I thought. They were liberal intellectually and politically. They themselves and how they were weren’t liberal. They tried to get me to understand it and I did, but they were firmly entrenched in their way of life. I was just waiting for the time I could do what I wanted to do.”

That time did not come immediately after graduation for Debbie. “I wanted to go to Europe, but I ended up going to a two-years girls’ school in Hackettstown, N.J. My parents didn’t think going to Europe was the right thing to do. I didn’t really want to go to school, but I did because I was very submissive. I didn’t know what else to do. I really had no idea how to take care of myself. I had been programmed for marriage and a certain degree of higher education. I don’t think my parents contemplated a future for me other than marriage. I was marketed for that, I was produced for that. This two years was to finish me off, to perhaps meet someone.”

Not finished, and without having met that certain someone, Debbie moved to N.Y. to “be an artist of some sort.” Straight jobs occupied her days for three years whole fooling around with music occupied her nights. Debbie attributes a secretarial job with the BBC as the initial encouragement for her experimentation with sound. “I hung out with jazz musicians. I met Bob Evans, the piano player. I met a lot of weird people like Tiger Morse, Tally Brown. I was living on St. Marks Place. They did jazz all the time. It was free, abstract, non-music music. Whenever it became music, it was music. Most of the time, it was noise–percussion, screeching, shit like that. I chatted and yelled and banged stuff and carried on. And then my friend who played guitar got a group together called Wind in the Willows.”

Wind in the Willows was an eight piece band that recorded one album for Capitol produced by Artie Kornfeld. Kornfeld produced Every Mother’s Son and the Cowsills and, in conjunction with Michael Lang, was responsible for the Woodstock festival. Late 60’s hippie music, the album features a dark-haired Debbie on finger cymbals and doing back up vocals. With Capitol’s backing, Wind in the Willows toured nationally, from Boston to L.A. and San Francisco. They opened for Melanie at F.I.T. with Zacherle as M.C. Difficulties in maintaining drummers caused a basic musical instability within the group that eventually caused their demise. “I was dissatisfied. I wasn’t turned on by the music, by what I was doing. I said we should make certain changes in the band. Paul didn’t agree, so I said, ‘Well, I’m out, you’ll have to get somebody else.’ They broke up.

The break-up, occurring in ’68, marked the beginning of a long period of confusion and depression. She lived in the East Village with one of the Willows’ drummers and supported herself by waiting tables at Max’s. Max’s was ruled by the vintage Warhol crowd at this time and, appropriately enough, they drove her bananas. “I used to cry a lot then generally. It wasn’t just them, they just trigered it off. They were very frustrating people to wait on. The only one I got friendly with was Eric Emerson and he was friendly with everybody, especially girls. I made it with Eric in a phone booth upstairs. One time only.”

The job at Max’s lasted for eight months until Debbie ran off with a multimillionaire to live in a Bel Air mansion in an orbit of B.P.’s (Roman Polanski and Warren Beatty) and Trader Vics. California dreamin’ quickly turned to a nightmare. Debbie stayed a month until she got fed up and hopped on a plane back to N.Y. “I was crazy. I was completely out of my mind. I was into junk, I was really fucked up. For a long time, it was pretty blank. For a long time, I tried to blank blocks of my life out. I did junk for about three years, right after Wind in the Willows broke up. I couldn’t stand the surroundings. I like the drug. I like the high, there’s nothing better, but I can’t stand the scene. You have to deal with extortionists. For awhile, I had this dealer living in my house on 107th and Manhattan Ave. and I nearly went beserk. That really finished me on the whole trip. These forty year old guys with guns and infections all over their bodies. I don’t think they ever went to the bathroom. I just quit. At the same time, I met this doctor on Central Park South who gave vitamin shots with amphetamine and I started doing that instead. And that was like bouncing off and going in another direction.”

She moved to a small art community outside of Woodstock to get away from the city and the drugs for four months. Then, it was back home with her parents in Hawthorne. “The idea of doing music haunted me everyday. I said to my family, ‘I think about doing this every single day.’ My mother never said not to do it, she just said, ‘Be practical.’ I worked in a health spa in Paramus teaching exercises.

One of the jobs Debbie had during this period was as a Playboy Bunny. “I was stoned most of the time. I was just there doing it. Some of those girls would make five hundred to a grand in two nights. I wanted the money. It was a goal and something I had always had held in front of me in my younger life. When you’re younger, you have idyllic dreams of things to do. I did it and it’s not so good. It’s pretty disgusting work. I stopped doing junk and I didn’t need the money as much. In a way, I used drugs to stimulate myself or control my state of mind to help me get through a rough, emotional time in my life. When I felt a little more secure, I was ready to go on as a person without any help, assured of what I was.

During this entire period, Debbie was unable to sing. “Everytime I tried I really wanted to do so badly, but I just couldn’t get it out, privately or in front of people.”

Lead guitarist for Blondie and boyfriend of Debbie since he was a black silhouetted stranger at a Stilletoes show, Chris Stein interjects, “You didn’t think you should be doing it because of your upbringing.”

“I had already done it before thousands of people with Wind in the Willows. I remember one concert before 3,000 people and it was a great rush. I loved it, it was a thrill. And then something happened. It’s deep seated, deep routed insecurity from childhood.” And then I just started coming back to the city and hanging out for awhile.” In ’72, the N.Y. Dolls began occupying the Mercer Arts Center and Debbie became one of the troops. “I worked as a beautician for a while. I heard from Janis with the red hair that Elda and Holly Woodlawn and Diane, who used to live with David, had a girl trio called Pure Garbage. I became obsessed with this. I saw Elda one night at Max’s and I said, ‘Oh, Elda, I heard you have a trio. I’d love to come and hear it sometime.’ And she said, ‘Well, it broke up.’ And I said, ‘Well, if you ever want another singer, call me.’ And that’s how I got back into doing it. Elda, me and Rosie Ross were the original Stillettoes. Tony Ingrassia was our director. He worked on the songs with us, concentrating on a mood, projecting a mood through a song, stage tricks to give us a cohesive look. He and Elda used to fight about the image. It was her concept. She wanted True Confessions trash, tacky.”

Debbie’s stint with the Stillettoes lasted two years off and on. “Three girls trying to get along together is hard enough without worrying about who’s ego is going to be on top. Elda wanted a certain person to manage us, and I didn’t like the idea of someone saying this is your manager sign this. I said I wanted to do my own thing again and I left.”

That was in the summer of ’73 and when she left, she also took the band with her. Debbie, Chris on guitar, Fred Smith on bass and Billy O’Connor on drums played around sporadically using various names like Angel and Snake. “Julie and Jackie sang back-up for awhile, then we took the name Blondie. I remember it fit together really well, because all three of us were blondes. Then right before our first gig, Jackie dyed her hair dark brown. That didn’t work out. They just wanted to do something.”

That first Blondie concoction lasted four months. Ivan Kral joined the main core of the band to fill out the sound, but only lasted for three months. “Ivan just got bored. That was the non-period of rock. TV, the Ramones and us were just playing around, but there was no publicity, no attention focused on anyone. Ivan was working at the Bleecker St. Cinema and he was always moving. He moved about three times in those three months.” After Kral left, the group was supplemented by two other female singers, Tish and Snookie. They lasted only two months longer than Kral did and also marked the beginning of Billy O’Connor’s going crazy. To complete the tragedy, Television asked bassist Fred Smith to join and Smith accepted. “I had an intuition with Fred. He was really unhappy at the beginning of the month. At the end of the month, we had a gig at CBGB and we played terrible the first set. I didn’t know what had happened, but during the break between sets, Fred had told Chris he was quitting to join Television. Our next set was worse. We had played a long time with Fred. We were struck dumb by the whole thing, by the whole movement against us. I may be paranoid, but I think that whole clique wanted to destroy us.”

“Those two sets had been drummer Clem Burke’s first with Blondie. Burke answered a Voice ad reading, “Freak energy rock drummer wanted,” and as the last auditioned of forty drummers, he struck platinum. “He was really out to work. After the thing with Fred happened, he pushed us really hard. He kept is going.” Within a month and a half, Burke had brought in a New Jersey jamming friend who had never formally joined any group. Gary Valentine joined Blondie on bass in August of last year and soon after, a word to The Fast at a Mothers’ engagement brought in keyboard player Jimmy Destri. “Jimmy had played with Milk ‘n’ Cookies for about two weeks right before they went to England to make their album for Island. But after he had learned all the material, just before they left for London, Justin said, ‘You can’t come.’ Jimmy got a full time job and went back to school and that’s where we found him.” Blondie was completed.

“I want to be a stylist. Certain people are stylists and certain other people are mechanists. I want to really do something. We’re struggling to get a sound and a style and make it a whole personal thing. Everytime we go onstage, I try to do something different. It’s like this process of elimination: something works and we keep it, it doesn’t work and we throw it out. It’s not finished yet, but we’re moving towards it. Like Patti Smith has her whole trip down pat. She has a very masculine and intellectual approach to music and performing. I don’t want to do that. I played a chorus girl, Juicy Lucy, in Jackie Curtis’ Vain Victory and I found that I liked music better because it’s not as intellectual as acting. Rock and roll is a real masculine business and I think it’s time girls did something in it. I don’t want to sound like a libber, but I want to do something to make people change the way they think and act towards girls. Janis Joplin did that, but she had to sacrifice herself. Everytime she went out on stage, she had to bleed for the audience. I don’t feel like I have to sacrifice myself.

“Right now, I want to sound like our live sound in the studio. I don’t want to do something on record I can’t do on stage, unless, you were going to do a complete number like become a Barry White or something. We’re not going to do that, obviously. We’re looking forward to having something on the radio by summer.”

“I think the strongest art comes from the strongest people, not the weakest ones. I didn’t think I was strong enough at one time, but I do now.”

Craig Gholson

__________________________________________

LATEST FLASH!

Blondie’s hopes to “have something on the radio by summer” are close to being realized. The group has one basic track and scratch vocals down on a single to be released in June. “Sex Offender,” written by Gary Valentine and Debbie will be backed with Debbie and Chris Stein’s “In the Sun.” The single (in the process of being recorded at Plaza Sound) will be released on Craig Leon and Richard Gottehrer’s newly formed Instant Records.